Exhibitry: Telling a landscape’s story

By John deWolf

As Canada’s sesquicentennial celebrations unfold this year, it has been important not to overlook pre-Confederation history and Aboriginal people’s heritage. By way of example, in an effort to help strengthen ties between the federal government and Saskatchewan’s Métis Nation, Form:Media recently ‘dressed’ Lot 47—site of the once-thriving village of Batoche in central Saskatchewan—with an environmental graphic design (EGD) project, which uses signs and related components to tell the tale of the settlement’s history.

The history behind the project

At the centre of this history is a dispute between two opposing methods of landholding: (a) a linear, river-oriented allotment by an agrarian people versus (b) a less natural grid-based system devised and imposed with a lack of regard for local geographic features. The story proceeded from non-issue to conflict to entente to formal collaboration.

For millennia, the Plains were traversed by Blackfoot, Cree, Ojibwa, Assiniboine, Nakota, Dakota and other First Nations. The South Saskatchewan River region, in particular, came to be seen as the physical, cultural and political home of the Métis Nation, which was formed through the mixing of Indigenous and European peoples and, as such, was distinct from Canada’s other Aboriginal peoples. In the late 19th century, a decline in the bison population diminished hunting for the Métis, forcing a transition from a semi-nomadic to an agrarian way of life. The consolidation of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company also meant fewer Métis traders were employed, so they made do by settling on the land.

In 1872, a small number of Métis from the Red River area near Winnipeg (then Fort Garry) established Batoche at the junction of the South Saskatchewan River and the Carlton Trail, a 1,500-km (932-mi) overland route connecting Fort Garry with Fort Edmonton. It was also near a third major trading route, the Humboldt Trail.

The town’s name was derived from its founder, Xavier ‘Batoche’ Letendre, who established Lot 47 with his home, a store and a ferry across the river. The approach taken to land division accounted for the importance of trade routes and the relationship of the settlement to the river.

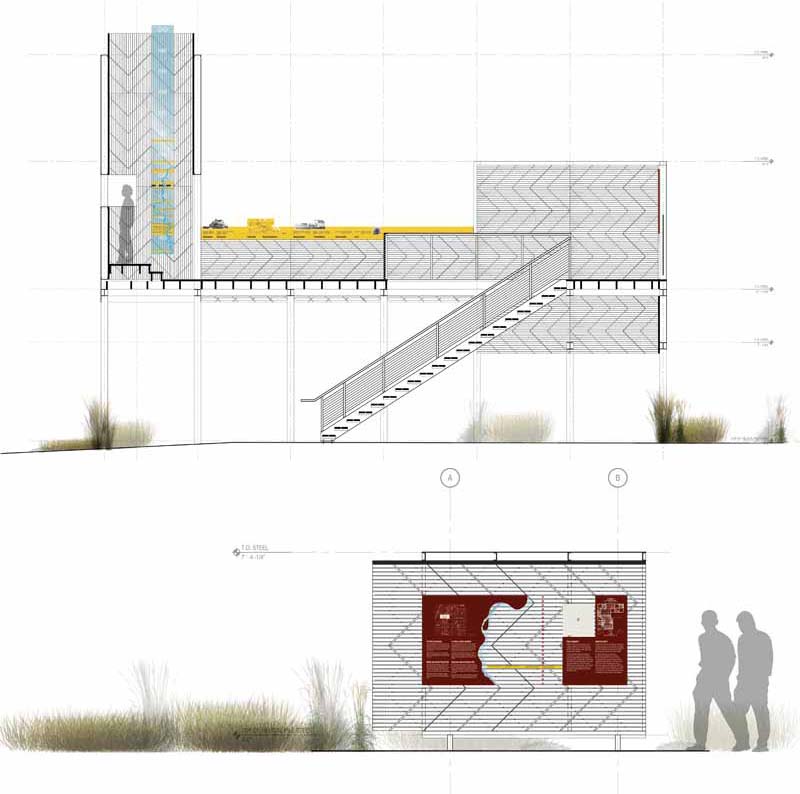

Drawings courtesy Form: Media

Inspired by French methods, the Métis divided the land so every family would have some river frontage. Most lots were about 200 m (656 ft) wide at the riverside and up to 3 km (1.9 mi) long. The settlers used just the riverside land at first for agriculture, then expanded inland to graze cattle, grow larger crops and tend woodlots.

Batoche quickly developed as the commercial centre of the overall settlement area, which was home to 800 residents by 1883 and 1,200 by 1885. It had come to be considered the heart of the Métis Nation.

After developing their own unique culture throughout the 19th century, the Métis were a strong, politically organized force in defending their rights. Throughout the 1880s, they came into confrontation with the newly established government for the Dominion of Canada over a variety of its policies.

In particular, the Métis—along with First Nations and white settlers—became concerned about their allotted properties being resurveyed and potentially redistributed under the federal government’s grid-based land survey, which was being conducted across Western Canada. After the government ignored their concerns, the Métis declared a provisional government of Saskatchewan—essentially an independent nation—in March 1885.

In response, the federal government dispatched the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP), the forerunner to today’s Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RMCP), to bring an end to what it considered a rebellion. Several battles, including a decisive one at Batoche in May 1885, led to the defeat of the short-lived provisional government.

Some Métis families dispersed as Batoche was subjugated and appropriated by a government that saw the village as a commodity over which to exercise its authority. Most left later due to disease and economic factors, such as the building of the railway, which bypassed the village altogether.

Yet, even as the Dominion tightened its control of Western Canada, the linear lots on the banks of the South Saskatchewan River remained, as a testament to the community’s resistance. Similarly, the Métis have flourished throughout Western Canada following their dispersion. Today, more than 400,000 people identify themselves as Métis.