Accessibility standards for signs

by all | 7 February 2014 8:30 am

[1]

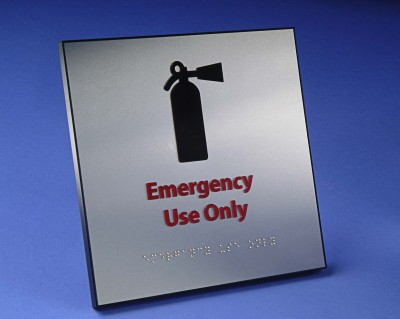

[1]Photos courtesy Nova Polymers

By Dave Miller

Unlike the U.S. and its well-established Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), Canada does not have a single, consistent, national standard for accessibility signage. There is federal legislation that requires public spaces to be made accessible to people with disabilities, but provinces, localities and agencies are also allowed to design their own codes and guidelines, some of which relate to sign designs, materials and installation procedures. So, it is important for signmakers to know which guidelines are pertinent to their projects.

Many different groups throughout Canada that choose to build their own codes start with the guidelines established by the Canadian Standards Association (CSA), a non-profit, membership-based organization charged with developing standards that anyone can use.

Specifically, they have turned to CAN/CSA-B651-95, Barrier-Free Design. Section 6.4 focuses on signage, including character proportion, contrast, illumination, tactile characters and access symbols.

CSA highlights

CSA’s tactile sign guidelines are applicable to regulatory, warning and permanent room-identification signs, while its visual guidelines are applicable to orientation and information signs. This approach is similar to that of ADA’s guidelines.

On the other hand, CSA guidelines allow both upper- and lower-case tactile letters, as opposed to the American requirement for upper-case only. The characters can be anywhere from 16 to 51 mm (0.6 to 2 in.) high and should be smoothly edged—as should the sign itself.

[2]

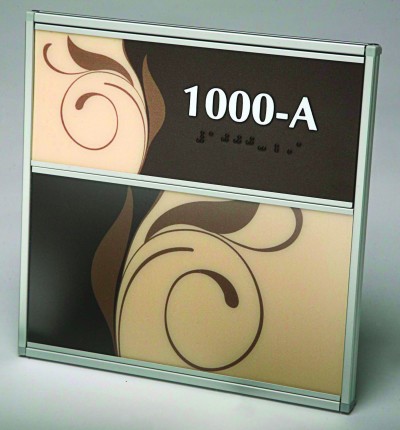

[2]CSA guidelines allow both upper- and lower-case tactile letters, as opposed to ADA’s upper-case-only approach in the U.S.

All characters, whether tactile or solely visual, should have minimum width-to-height ratios of 3:5 to 1:1 and must have a minimum stroke-width-to-height ratio of 1:5 to 1:10. All symbols should meet international standards and be displayed within a minimum 150-mm (5.9-in.) field, with corresponding text and braille below them.

Sign heights are recommended at 1.5 m (59 in.) off the ground or floor surface. If at all possible, the sign should be placed on the latch side of a door, with a minimum clear area of 76 mm (3 in.) from the door’s frame. The sign should also be, at minimum, 140 mm (5.5 in.) away from the adjacent wall surface.

There are no colour-specific contrast recommendations, but a minimum lighting level of 200 lumens per square metre (lm/m2) is required.

Developing codes

The following are some examples of current codes and guidelines that have been built off of CSA’s work:

ODA

In Ontario, the still-evolving Ontarians with Disabilities Act is currently in the process of developing sign guidelines that can be incorporated into municipal codes throughout the province. In the meantime, some municipalities have gone ahead and developed their own codes.

FIP

The Federal Identity Program (FIP) has developed a set of standards for use in federal buildings based on CSA’s Barrier-Free Design guidelines. The FIP Manual includes Section 4.3B, Tactile Signage: Sign System and Installation Guide.

While multilingual standards are not included in CSA’s guidelines or ODA, federal sign programs are required to display both English and French, including all tactile information and braille. These requirements may also be applicable in some provincial or local codes. There are a number of sign systems with template-based approaches to multilingual accessibility.

[3]

[3] [4]

[4] [5]

[5]Permanent room-identification signs are covered under CSA’s tactile sign guidelines.

CNIB

The Canadian National Institute for the Blind (CNIB) has established best practices and additional guideline language that can be incorporated into local codes.

CTA

The Canadian Transportation Agency (CTA) has adopted its own set of accessibility signage guidelines for transportation facilities, including airports, train stations, marine facilities and interprovincial bus stations.

IBC

While CSA’s general guidelines are in the process of being adapted for ODA and FIP and, indeed, are already the most commonly used in Canada, it is worth noting individual agencies and municipal governments are free to alter these guidelines. For example, another resource for municipalities to base their sign codes on has been the International Building Code (IBC), which provides detailed information in this area. ADA was also partly based on IBC.

Many Canadian code guidelines are currently moving toward harmonization with IBC. Where CSA’s standards are in effect and there is no local code, it may even be possible to substitute IBC’s information.

Visual character guidelines, for example, are closely aligned with IBC, including colour contrast levels, letter heights and minimum viewing distances, as well as specific ratios for width-to-height and stroke-width-to-height ratios.

Braille

The primary difference between Canadian and American accessibility signage, however, is how they use braille. Grade 1 braille, which complies with the Unified English Braille Code (UEBC) and also meets multilingual standards, is used in Canada.

In this form, which is not used on signs in the U.S., all letters and numbers are given a braille equivalent. For this reason, Grade 1 braille takes up a significant amount of space on a sign, which can potentially limit how much information is displayed.

Dave Miller is business director for Nova Polymers, which manufactures and distributes photopolymer-based sign products, and sits on the board of directors for the International Sign Association (ISA). For more information, visit www.novapolymers.com[6].

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/PB150433.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/YA125.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/1000-A-trans.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/401.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/inpro6-copy.jpg

- www.novapolymers.com: http://www.novapolymers.com

Source URL: https://www.signmedia.ca/accessibility-standards-for-signs/