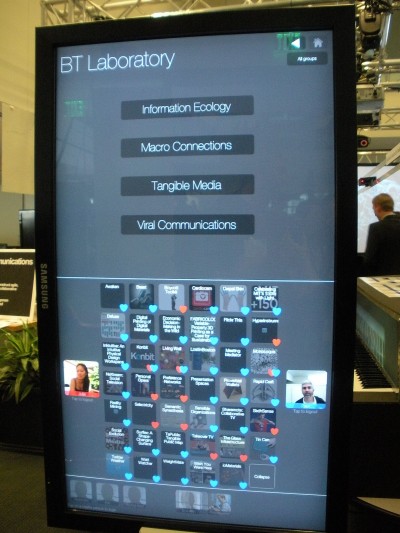

As mentioned, the system’s interaction and data model is designed to encourage the exploration of links between people and their projects. When two existing users log on to the same screen, for example, any items they have in common are highlighted. Indeed, one of the core social innovations of the GI user experience is the successful encouragement of sharing a single screen.

The kiosks were context-dependent, displaying information relating to the screens’ specific locations and the user(s) standing in front of them.

After leaving the Media Lab, users can also access a ‘portfolio’ on the Internet with a log of their activities, listing the items in which they were interested and the people with whom they shared the screens. This makes it easier for them to connect later with researchers and other people they met while interacting with the system.

The future of kiosks?

When conceptualizing GI, the MIT researchers considered two general forms of kiosks:

- Utility-based kiosks designed to accomplish or ‘incentivize’ certain tasks.

- Information-based kiosks designed to provide contextual access to digital content.

GI fills both of these roles with custom displays based on the user’s physical location that promote exploration and social interaction.

One project that shared several concepts with GI was the United States Library of Commerce’s deployment of information kiosks that allow patrons to identify specific artifacts and associate them with their personal accounts, which can later be accessed at home through a dedicated web portal.

Another was a Pepsi kiosk system that allowed consumers to receive incentives based on how much they personally recycled. Users logged in via touch screen and their physical recycling inputs at a kiosk were immediately reflected in their accounts. Kiosk location was not an important factor in this case.

A third precedent was a college campus kiosk system that detected nearby students’ RFID badges, looked up their classes and helped direct them to their next destination. These units were installed at two locations and could personalize data based on maps and students’ schedules, but there was no way for users to update that data at the kiosk itself. The information transfer was unidirectional.

One innovative aspect of the project was how it successfully encouraged multiple users to share a single screen.

GI was initially deployed in the MIT Media Lab building in May 2010, in time for the facility’s spring sponsor event, which was attended by approximately 1,000 people, including students, faculty, staff and representatives from nearly 100 companies. With crowds of people gathering around the displays, it quickly became clear GI activity would be clustered around such events.

The next biannual sponsor event was in October 2010, which saw a relative increase in visitor engagement, evident from statistics recording use. The absolute number of navigation interactions decreased, but there were more logins at multiple locations by the same users, more ‘co-logins’ involving more than one person and more in-depth exploration of the displayed information.

Since the initial deployment, the MIT Media Lab has built a prototype for a financial software company, to help its employees connect their own ideas, and installed another GI screen at a bank’s headquarters (HQ) to better enable users there to navigate changing projects. And for the lab network itself, the researchers decided to incorporate additional ‘ad hoc’ social networking for sponsors, updating the AI to recommend not only projects each guest should visit, but also other people he/she might want to network with or visit.

Chaki Ng is an interaction technologist and entrepreneur who worked on the MIT Media Lab’s Glass Infrastructure (GI) project. For more information, visit www.media.mit.edu.