Digital Wayfinding: Identifying the lessons learned from museums, healthcare, and transit experiences

Broadening the definition of wayfinding

Today’s technology expands upon the traditional definition of wayfinding, from finding one’s way to finding meaning along the way and context at the destination.

Urban planner Kevin Lynch defined the term ‘wayfinding’ in his seminal book Image of the City, published in 1960. To paraphrase, he characterized wayfinding as “definite sensory cues from the external environment [such as] maps, street numbers, route signs, and bus placards.”

Lynch’s original ideas about how one deciphers their surroundings resonated with architects and designers, and effectively cultivated a new discipline in the gaps between the two professions: experiential graphic design (EGD).

The first generation of EGD practitioners focused on those traditional cues of maps and signs, codifying best practices to orient and guide visitors. Over time, they widened their domain to ‘placemaking,’ making the places one visits distinct and memorable.

With the debut of the smartphone, the definition of wayfinding has once again evolved. At its core, wayfinding’s role is still to guide visitors to their destination easily and efficiently. But now, a smartphone’s sensors and apps can infuse meaning along the journey and helpful, contextual tools upon arrival.

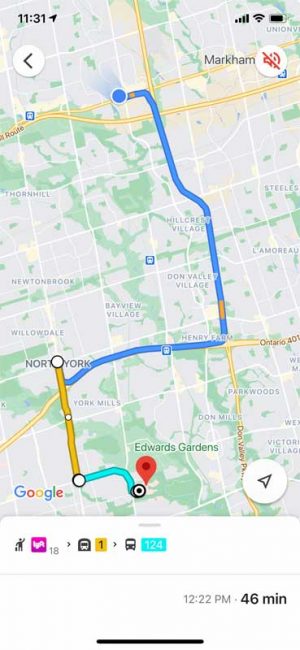

In general, when one navigates, they look for the shortest, most efficient route—wayfinding apps address time-driven needs by routing users around traffic, highlighting the closest gas station, and directing them to the fastest transit option. It is no surprise transit apps are the most innovative and popular wayfinding apps.

However, when one meanders through a park or visits a museum, efficiencies do not drive most users—instead, they want to get the most out of their sojourn.

For example, in museums, wayfinding has become inseparable from the institution’s mission to enlighten and illuminate the collection. The term ‘playfinding’ highlights how people wander and explore environments like museums (and parks or cities), in a less directed and more serendipitous manner. Playfinding apps and interactive screens reveal the secrets of the place as one navigates: such as the history of an artifact or the biography of its maker.

In a hospital, wayfinding’s role is explicit and necessary, but subordinate to the main reason for the visit: medical care. In these facilities, wayfinding is most effectively expressed within the personal context of the visit. For example, a hospital’s app may list a patient’s appointment with ‘get directions’ or ‘closest parking options.’

These new tools—whether pre-trip planning on a home computer, smartphone app, or on-site digital signs and kiosks—inspire a new level of confidence in navigating. Users are assured they will get to their destination without getting lost. And if they do get lost, they are equipped to find their way.

Armed with these convictions—and with a smartphone in their pocket—perhaps one can find deeper meanings along the journey.

Lessons learned

What can one learn from this generation of digital wayfinding technology? There are useful insights to be gathered from both

the user’s perspective and that of the institution offering the tools.

User experience

1. Blend physical and digital wayfinding into one cohesive experience. The Art Institute’s JourneyMaker, a digital tool that allows a family to create their own tour of the museum, is a good example of blending the digital (designing one’s tour at the touch tables) and physical (following a paper guide to the tour stops, referring to signs along the way.) Digital tools create the custom tour and traditional tools guide the way.

It is critical all wayfinding tools share the same vocabulary and iconography to make the journey as seamless as possible.

2. Look for ways to provide context along the journey. Today’s broader definition of wayfinding demands one incorporates contextual information and features. What information could visitors use to make their experience in the environment more efficient, more rewarding, or more memorable? Something as simple as locating the nearest restroom is a practical, relevant feature most digital wayfinding tools lack today. It is also important to note visitors benefit from pre-trip planning tools that equip them with helpful information even before they leave home.

3. Lessen the cognitive load. Navigating takes attention, and the latter is in short supply in today’s chaotic world. Cluttered interfaces, stuttering blue dots, and dense maps are confusing to use. When faced with too much information, most visitors abandon the tool and ask a human to show them the way.

Most of today’s indoor blue-dot wayfinding apps ask too much of their users, resulting in unsatisfying interactions. Scale is also an issue. While the technology enjoys a ‘cool factor,’ it has not achieved real-world usability yet.

4. People are willing to try new things in low-risk situations. As Andrea Montiel De Shuman at Detroit Institute of Arts found, people are not intimidated by new technology if they are encouraged to play in congenial environments like the museum. One thrilling interaction like spying inside a sarcophagus can overcome any technical hiccups.

These are the early days of wayfinding technology, and today’s experiments will inform tomorrow’s ubiquitous tools. Just as one learned to use their car’s GPS and MapQuest in the 1990s, today, users can navigate confidently with the maps app on their phones.

5. ‘Right-size’ the technology for visitors and the environment. Digital signs deliver real-time arrival information to commuters

at stations and on buses. Mobile-optimized websites have been the lowest-friction way for some airports to offer information to their transitory visitors.

Apps are frequently the wrong answer. The sheer difficulty of promoting an app to visitors, reminding them to use it, and keeping it relevant in the over-populated app universe can rarely be overcome by its usefulness.

Usage statistics confirm the top five apps (Facebook, Facebook Messenger, YouTube, Google Search, and Google Maps) account for 80-90 per cent of total app usage.

In today’s smartphone era, touchscreen kiosks only make sense in very specific use cases. People prefer to find answers and directions on a device they carry and can refer to as they travel.