Expanding the glass canvas

by all | 24 September 2013 8:30 am

[1]

[1]Photo courtesy Brian R. Savage

By Brian R. Savage

In the past, when architects wanted to add printed design elements to the glass ‘skin’ of a building, they were limited to one- or two-colour screenprinting or digital printing technologies with difficult organic-based inks. Today, however, ceramic-based inks are allowing for a more controllable digital printing process and yielding durable, long-lasting, full-colour graphics.

Screenprinting has usually been considered the most cost-effective method for adding graphics to architectural glass when only one or two colours are to be printed in a repeating pattern across many glass units. The screens themselves, however, can be cost-prohibitive and are limited in terms of the number of prints they can produce before the end of their useful life.

Digital printing can be thought of as a complement to analogue options and may not be ideal for all circumstances, but it does help remove some earlier barriers, particularly by supporting multiple colours within a complex design.

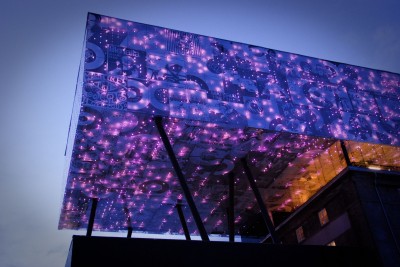

Today, a new generation of digital printers is giving designers the opportunity to turn what was once simply the functional façade of a building into an ornate canvas. In some cases, they can even use the technique to optimize the solar performance of the façade.

[2]

[2]Otherwise plain façades can now be decorated cost-effectively with digital printing. Photos courtesy Dip-Tech Digital Printing Technologies

Ink flexibility

There are different types of digital printing processes for the architectural glass market. The two main differences between techniques are the types of ink used and how the machines transfer the ink onto the glass substrate.

Inkjet printers with drop-on-demand technology use a programmable printhead that traverses back and forth just above the substrate. Each colour of ink has a dedicated grouping of nozzles on the printhead, which can be individually activated to ensure ink drops reach the substrate in their proper locations.

For printing on glass, the main ink options include organic ultraviolet-curable (UV-curable), inorganic ceramic and other specialized inks intended for printing interlayers in laminated applications.

In the past, the physical properties of the ceramic frit—i.e. the design to be adhered to the glass substrate—made it difficult to use with an inkjet printer, as particles within the frit had a corrosive effect on the printhead. Such drawbacks have since been addressed and there are now ceramic inks that are practical for use in digital printers.

With the flexibility of today’s digital printing, it can be used with a ‘monolithic’ glass substrate or with laminated glass and insulating glass units (IGUs). Solar control coatings, for example, can be applied directly over the print to improve the solar performance of a glass façade. In addition to exterior façades, digitally printed glass can be incorporated into interior dividing walls, office walls and, of course, signage.

The current versatility and resolution capabilities of ceramic inks support more types of graphics than in the past, including photorealistic images, legible text and texture patterns to simulate wood grain, granite and marble. Also, the transparency and opacity levels of the graphics are controllable.

With ceramic inks, digitally printed glass can be cleaned and cared for in the same manner as other types of glass. As a general rule, if something could harm the glass, then it could harm the print—but in most of these architectural applications, the graphics are permanently protected within an insulating or laminated unit.

Characteristics of ceramic inks

The ceramic inks used in digital printing are similar in nature to the frit used in screenprinting. They behave and perform almost identically. The main difference is the inks are produced using smaller particles, allowing them to flow through the printhead onto the substrate, and they contain inorganic pigments that help keep them colour-stable over the lifetime of the printed image. Also, ceramic inks used in North America are free of heavy metals like cadmium or lead.

[3]

[3]Each image digitally printed onto the glass façade of Norway’s Rockheim Museum is unique, so screenprinting would have been cost-prohibitive.

A wide colour gamut can be achieved by mixing base inks through either of two methods: premixing or ‘digital mixing’ during printing. Premixing is useful when only a few colours are involved or when a particularly smooth appearance is required for interior signage.

With digital mixing, on the other hand, distinct variations in colours are achieved by placing drops of different inks next to each other. The concept is similar to a TV screen, which uses red, green and blue (RGB) pixels that appear separate from another when viewed up close, but form other colours and full images when viewed from farther away.

Inks can be applied in various quantities and thicknesses to achieve various results. Blue ink, for example, tends to be more translucent than other colours, so a blue-heavy graphic may allow greater light transmission into a building’s interior during the day and out to the exterior during the night. A façade can take on a stained-glass effect.

The printing process

The digital printing process begins, of course, with the production and manipulation of electronic design files. Both raster- and vector-based images can be used for ceramic frit inkjet printing, depending on the project’s requirements.

Compared to screenprinting, digital ceramic inks have low viscosity. This enables higher-resolution graphics to be achieved. At thicker opacities, care must be taken not to blur the printed image.

The image files may be designed individually for each pane of glass or an entire façade may be designed as a single large file and then ‘tiled’ across multiple panes. Software for this purpose is usually printer-specific and can also handle adjustments to allow for mullions and holes in point-supported glass, to ensure an image appears seamless from one pane to the next.

Raster image processor (RIP) software turns the image into multiple layer files for each of the base ink colours. A purple graphic, for example, is processed into blue and red layers. There may also be multiple levels of the same colour.

Once these colour layer files are sent to the printer, the image is interpreted and ceramic inks are deposited onto the glass substrate. Generally, the printed glass is then sent through a tack oven to dry the inks, but some newer-generation presses are able to dry the inks as the image is being printed.

At this point in the process, although the inks are dried, they carry a matte finish and have not yet been permanently adhered to the glass substrate. For that step, the printed glass must go through a separate heat-treating oven.

[4]

[4]The exterior of AFIMall City in Moscow, Russia, is exemplary of how enormous graphics can be integrated into architecture.

The glass is heat-treated, tempered or even bent to specifications. The oven fires at temperatures of 600 to 670 C (1,112 to 1,238 F), depending on its setup, which permanently affixes the image to the glass, with a glossy finish.

From here, the printed glass can be directed to other processes in the production line, including coating application, laminating and insulating. If it is to be used in an interior application, however, it might instead be left in its current form.

Benefits and limitations

The benefits of digital printing over screenprinting on glass can include cost savings, greater design flexibility and easier repeatability. In addition to the ability to produce custom images with many colours, digital printing can incorporate micro-lines, micro-dots and dual images (i.e. two different graphics that can be seen from either side of a single pane of glass, even though they have been printed on the same surface).

Another advantage is the design files for digital printing are stored electronically, with none of the typical storage costs of screens. Graphic replacements and reproductions can be printed years later with dependable results.

[5]

[5]Inkjet printers with drop-on-demand technology use a programmable printhead that traverses back and forth just above the glass. Photos courtesy Brian R. Savage

There can still be challenges. From an architectural perspective, calculating a façade’s solar performance can be difficult because, as mentioned, different ink colours will transmit light and heat at different levels, even within a single pane of glass.

Matching the appearance of the actual graphics to the designer’s vision can also be challenging, for the same reasons. The amount of light being transmitted and reflected during a sunny or cloudy day or at nighttime will affect the way images are perceived. Applying a coating over the graphics can also mute the vibrancy of their colours.

For that matter, the choice of glass substrate can cause graphics to appear differently than designed. Regular clear glass often adds a green hue, which a lower-iron glass may help subdue. All of these issues need to be taken into account when designing the graphics in the first place. With electronic design file manipulation for digital printing, it is possible to make adjustments to compensate for such factors as solar performance, light levels and privacy.

[6]

[6]If an image will be tiled across multiple panes, adjustments must be made to allow for mullions and any other interruptions.

Vision versatility

The architectural market represents a source of constant demand for designers to leave their mark on buildings at a grand scale. As digital printing has emerged as a versatile, colourful way to define architects’ visions on a building’s façade and on interior walls, it can mean significant opportunities for sign and graphics shops as suppliers to this market.

With ceramic inkjet printing systems, they are equipped with the software and hardware to fine-tune graphics to optimize solar control, privacy and other functional aspects of architecture, as well as achieve esthetic aims. And architects will appreciate the durability of ceramic frit applications, which have already been used in their field for years.

Brian R. Savage is a product manager at Viracon, an architectural glass fabricator. For more information, contact him via e-mail at bsavage@viracon.com[7].

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Digital-Print-Window-From-Exterior.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/ZAC-Euralille-France.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Rockheim-Norway.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/AFI-Mall-City-Moscow.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Digital-Print-Print-Head-Printing-Text.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Digital-Print-Software-Tiling-Example-Page-3-Para-5.jpg

- bsavage@viracon.com: mailto:%20bsavage@viracon.com

Source URL: https://www.signmedia.ca/expanding-the-glass-canvas-2/