Finishing: Pitfalls and opportunities for digitally printed fabrics

by all | 3 April 2017 10:30 am

[1]

[1]Photos courtesy MCT

By Steve Aranoff

Fabric represents the fastest-growing market segment for grand-format printing, including both commercial and industrial applications. When the time comes for finishing, however, fabric presents some special challenges, due to the material’s stretch characteristics, porosity and weight.

By way of example, a porous fabric cannot be held down on a vacuum table like vinyl can, so it is harder to keep in place when cutting it to shape with traditional mechanical knife tools. Similarly, digital vision registration systems can run into significant issues when attempting to ensure the proper portion of a printed graphic is contained within the cut area—e.g. when determining how to continue cutting banners that are longer than the finishing table, due to the extreme degree to which they stretch. Also, fabric rolls that are extremely heavy and bulky—which makes it even harder to cut the material cleanly and accurately by hand—call for motorized handling capabilities to unroll the fabric onto the table.

Production department capacity is also a major issue. Industrial and retail projects may involve many types of fabrics being printed up to 3 m (10 ft) wide, raising the question of how they are to be cut and finished accurately and economically, within an already-busy organization. Keeping both quality issues and turnaround time in mind, automated precision cutting has become a must. There are several approaches, however, each with its own benefits and drawbacks.

From print to cut

Print-to-cut vision technology was invented in the late 1990s and adopted across many brands of cutters. Workflow software was developed with major raster image processor (RIP) providers so as to output ‘cut’ files and automate the process after printing.

Over the years, these capabilities provide the impetus for more digital cutters to enter the growing grand-format printing marketplace. And since 2015, entirely new methodologies have enhanced print-to-cut vision accuracy specifically for fabric, with advanced features added to cut stretchy substrates more rapidly and accurately.

[2]

[2]Today’s projects may involve a variety of fabrics printed at a large scale, raising the question of how they are to be cut and finished accurately and economically.

Photos courtesy PNH Solutions

Driven wheel

A ‘driven wheel’ rotary system is a cost-effective method for finishing a variety of textiles. A motor-driven decagonal (i.e. 10-sided) blade chops through each fibre or thread, so as to reduce friction and drag while cutting.

“We researched what to buy for fabric finishing for a long time,” says Francois Hudon, managing director for PNH Solutions, an outdoor marketing, exhibit and fabric printing company headquartered in Montreal. “We visited multiple vendor sites and looked at workflow and support before finally deciding to buy a driven wheel cutter. It has been good for us and, with our increased volume, we will add a second as soon as we move to our new facility in early 2017.”

While some firms are completely digitally oriented for fabrics, the ability to handle other substrates may also be important. In PNH’s case, after buying a driven wheel system for fabrics, the company added a drag knife for vinyl.

Laser

Laser cutting has also been introduced in recent years to help seal the edges of fabrics. A liquid-cooled carbon dioxide (CO2) laser with intensity control can avoid leaving dark edges in most fabrics.

“We have other cutting tables, including one with a driven wheel, but the capabilities of laser really made the decision to buy it easy for us,” says Jason Ahart, chief operating officer (COO) for Olympus Group, a custom large-format digital printing and mascot uniform manufacturing company. “The laser can handle all of our large- and grand-format dye sublimation fabric cutting needs. And today, almost all of our other fabric cutting is done on the laser system, too.”

In addition to avoiding the frayed edges that can come with traditional knife cutting and routing capabilities, the fine nature of a laser is advantageous for precision-cutting graphics with small inside and outside arcs. With contactless systems, the laser does not cause any bulges in the material and can guarantee filigree (i.e. delicate) cuts right from the beginning.

“Our 3.2-m (10.5-ft) wide laser cutter was definitely the correct decision,” says Mike Lecus, president of Imagine Express, which specializes in large- and grand-format ultraviolet-curing (UV-curing) printing and dye sublimation, as well as small-format digital and offset printing. “It’s a solid machine that paid for itself in just a few months. We can laser-cut and get finished edges on most of our polyester-based fabrics as fast as we could with the driven wheel. And because of increasingly varied shapes being cut in fabric, including notches, we now only do rectangular cutting with the driven wheel and all the rest on the laser.”

While lasers can finish a broad variety of flag fabrics, meshes, satins and knitted textiles, they do have limits. They may not be able to cut fabrics coated in polyvinyl chloride (PVC), heavy-duty fabrics for doubled-sided printing, heavy weaves and fabrics containing cotton.

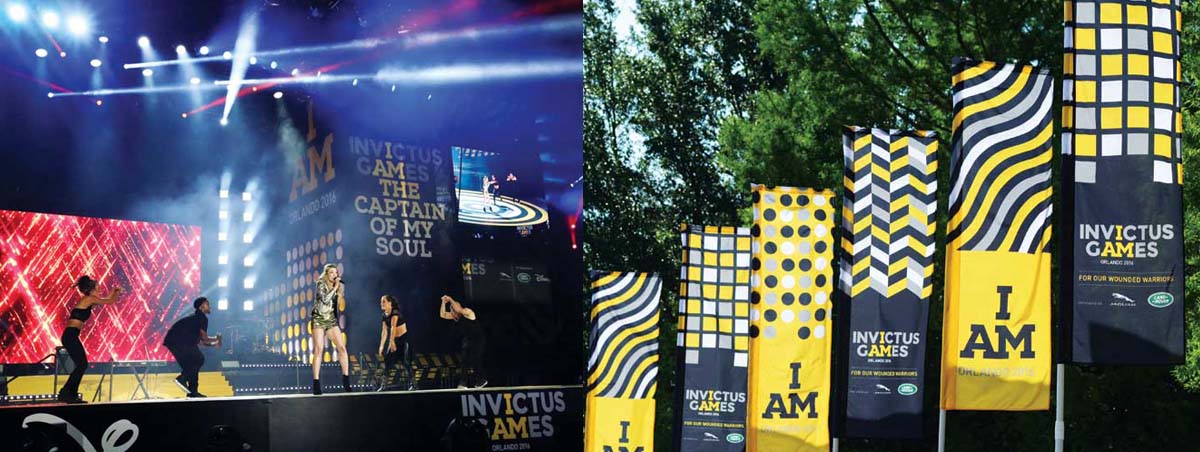

[3]

[3]PNH has also provided banners and backdrops to preview the Invictus Games, which will take place in Toronto in September.

All-in-one

Given the limitations of lasers, it is worth noting dual conveying capabilities are also available for fabric finishing, combining both laser and driven wheel technologies. This way, a single machine can do ‘double duty’ work for customers who require different types of fabrics.

“We’ve had a flatbed laser and driven wheel cutter operating for two years now,” says Jim Barss, vice-president (VP) of manufacturing for Comfortex Window Fashions, a Hunter Douglas company that custom-fabricates shades, shutters, blinds and other window treatments. “We achieved payback within roughly seven months.”

When Comfortex started using the machine, it was evolving from an already semi-automatic process, rather than straight from hand cutting. Today, the company runs the system in two to three shifts per day, up to six days per week.

With an ‘all in one’ system, shops can use a laser for cutting fabric or acrylic and a knife or router tool for other materials. This is useful given how many materials beyond fabrics continue to support industrial and retail graphics, including aluminum, semi-rigid plastics, composite materials, cardboard, foams and banner materials.

Steve Aranoff is vice-president (VP) of sales and marketing for Mikkelson Converting Technologies (MCT), which develops digital cutting systems, software, automation, tools and consumables for the. This article is based on a seminar he presented in December 2016 at an educational conference co-sponsored by the Specialty Graphic Imaging Association (SGIA) and the American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists (AATCC). For more information, contact him via e-mail at steve@mctdigital.com[4] and visit www.sgia.org[5] and www.aatcc.org[6].

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/fabric_IMG_1099-e1490641556965.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/edit1-3.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/edit2-1.jpg

- steve@mctdigital.com: mailto:steve@mctdigital.com

- www.sgia.org: http://www.sgia.org

- www.aatcc.org: http://www.aatcc.org

Source URL: https://www.signmedia.ca/finishing-pitfalls-and-opportunities-for-digitally-printed-fabrics/