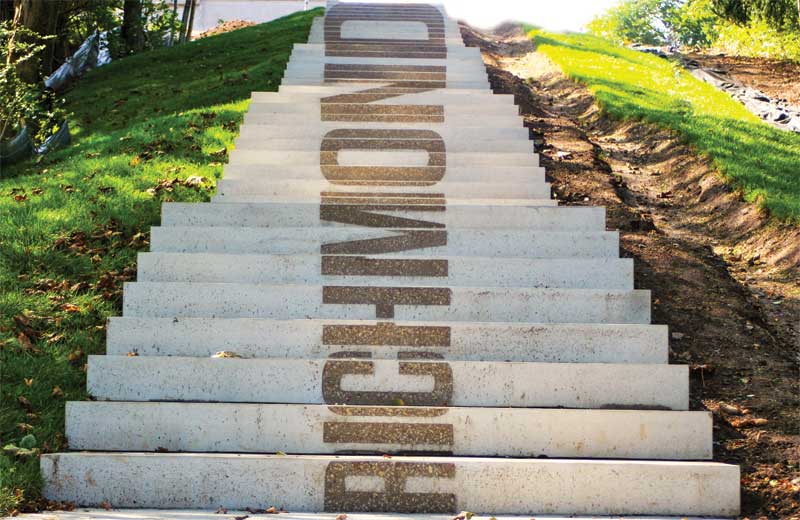

Graphically imaged precast concrete

By John Carson

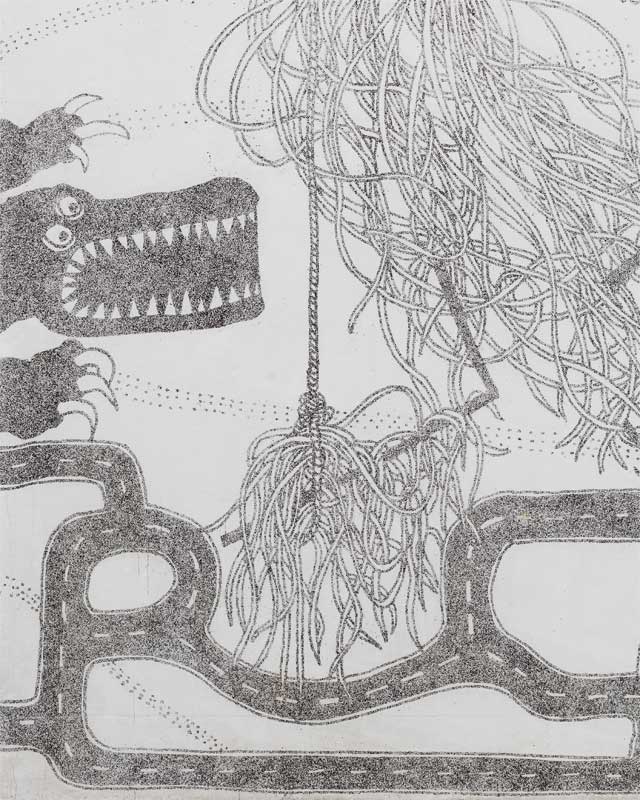

When artist Rebecka Bebben Andersson proposed installing a work called “No Smoking!” on the side of the Långbrodal school addition in Stockholm, Sweden, she was visualizing something much grander than a two-word sign. Her artistic rendering of a crocodile, gorilla, and other fun elements front the playground and reflect both the chalkboard inside and the wider world outside the school. Together, they communicate the school’s values, forward-thinking goals, and emphasis on student development.

What’s more they are, in a sense, ‘set in stone.’ This is because the artwork on the structural addition to the school, designed by Aperto Architects, was created using a technology that enables images and patterns to be placed onto precast concrete walls. Designers wanted a way to balance the permanence of affordable concrete with the daydreaming and visionary elements that are part of education.

The precast imaging technology has been used for nearly 15 years in Europe and Asia because of its relatively low environmental impact, ease of use, and esthetic versatility. These characteristics, combined with the many advantages of precast concrete, have spurred interest in North America, where the technology is available through the precast manufacturers in AltusGroup, a partnership of 19 precasters dedicated to innovation and collaboration. (AltusGroup members in Canada include Strescon Ltd., Saramac, and Armtec).

Precast concrete a strong medium for iconic visuals

When considering the use of this technology, it is critical to recognize the images can only be created on precast concrete and are intrinsic to its production process. Further, this finish (a membrane used in the prefabrication process of concrete) should be viewed as permanent signage—an integral part of a wall that incorporates the visual representation of a design esthetic, idea, or brand.

This method of placing images and patterns onto precast concrete was invented by interior architect Samuli Naamanka. He conceptualized and developed a method for imprinting a membrane with a surface retarder that affects how the face of the concrete cures. Therefore, a basic understanding of precast concrete is necessary to understand how the technology works and how it is applied.

Precast concrete walls are produced in a factory away from the jobsite—typically within 800 km (497 miles) for ease of transport and a reduced carbon footprint. The production process is carefully monitored; environmental conditions are controlled for optimum quality and uniformity. Since precast walls are typically fabricated under cover, weather will not impact the project as it would in the field.

Concrete is made of cement, aggregate, and water. The cement is typically white or grey, but pigments may be added during the process to realize a spectrum of colours. The aggregate can range from very fine sand to large (even rugged) stone and every size in between. Aggregate imparts additional esthetic value. It can vary widely in colour and texture and can either complement or contrast the cement colour depending on the desired visual outcome.

Precast walls are produced using a wooden or steel form, or mould, into which wet concrete is poured. The concrete membrane with the surface retarder is placed face up in the base of the form, and the concrete is cast on top. After curing and extraction from the form, the areas on the surface where the concrete was exposed to the imprinted retarder can be washed away using high-pressure water, revealing an image resulting from the contrast between the fair faced (smooth) surface and the exposed aggregate surface.

The amount of definition in the design can be controlled by the strength of the retarder and the colour variation between the cement and aggregate. Though it cannot be reused, the membrane is recyclable.

The resulting finish is just as low-maintenance—and permanent—as any other precast concrete finish.