Graphically imaged precast concrete

by | 16 November 2018 2:47 pm

By John Carson

[1]

[1]

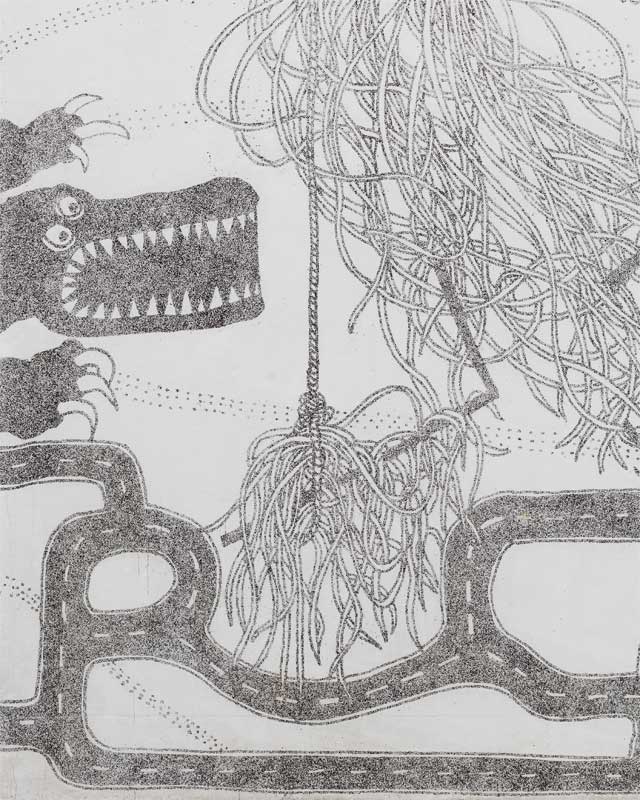

When artist Rebecka Bebben Andersson proposed installing a work called “No Smoking!” on the side of the Långbrodal school addition in Stockholm, Sweden, she was visualizing something much grander than a two-word sign. Her artistic rendering of a crocodile, gorilla, and other fun elements front the playground and reflect both the chalkboard inside and the wider world outside the school. Together, they communicate the school’s values, forward-thinking goals, and emphasis on student development.

[2]

[2]Rebecka Bebben Andersson’s artistic rendering of a crocodile, gorilla, and other fun elements front the playground and reflect both the chalkboard inside and the wider world outside the school.

What’s more they are, in a sense, ‘set in stone.’ This is because the artwork on the structural addition to the school, designed by Aperto Architects, was created using a technology that enables images and patterns to be placed onto precast concrete walls. Designers wanted a way to balance the permanence of affordable concrete with the daydreaming and visionary elements that are part of education.

The precast imaging technology has been used for nearly 15 years in Europe and Asia because of its relatively low environmental impact, ease of use, and esthetic versatility. These characteristics, combined with the many advantages of precast concrete, have spurred interest in North America, where the technology is available through the precast manufacturers in AltusGroup, a partnership of 19 precasters dedicated to innovation and collaboration. (AltusGroup members in Canada include Strescon Ltd., Saramac, and Armtec).

Precast concrete a strong medium for iconic visuals

When considering the use of this technology, it is critical to recognize the images can only be created on precast concrete and are intrinsic to its production process. Further, this finish (a membrane used in the prefabrication process of concrete) should be viewed as permanent signage—an integral part of a wall that incorporates the visual representation of a design esthetic, idea, or brand.

This method of placing images and patterns onto precast concrete was invented by interior architect Samuli Naamanka. He conceptualized and developed a method for imprinting a membrane with a surface retarder that affects how the face of the concrete cures. Therefore, a basic understanding of precast concrete is necessary to understand how the technology works and how it is applied.

[3]

[3]When artist Rebecka Bebben Andersson proposed installing a work called “No Smoking!” on the side of a school in Stockholm, Sweden, she visualized something much grander than a two-word sign.

Precast concrete walls are produced in a factory away from the jobsite—typically within 800 km (497 miles) for ease of transport and a reduced carbon footprint. The production process is carefully monitored; environmental conditions are controlled for optimum quality and uniformity. Since precast walls are typically fabricated under cover, weather will not impact the project as it would in the field.

Concrete is made of cement, aggregate, and water. The cement is typically white or grey, but pigments may be added during the process to realize a spectrum of colours. The aggregate can range from very fine sand to large (even rugged) stone and every size in between. Aggregate imparts additional esthetic value. It can vary widely in colour and texture and can either complement or contrast the cement colour depending on the desired visual outcome.

Precast walls are produced using a wooden or steel form, or mould, into which wet concrete is poured. The concrete membrane with the surface retarder is placed face up in the base of the form, and the concrete is cast on top. After curing and extraction from the form, the areas on the surface where the concrete was exposed to the imprinted retarder can be washed away using high-pressure water, revealing an image resulting from the contrast between the fair faced (smooth) surface and the exposed aggregate surface.

The amount of definition in the design can be controlled by the strength of the retarder and the colour variation between the cement and aggregate. Though it cannot be reused, the membrane is recyclable.

The resulting finish is just as low-maintenance—and permanent—as any other precast concrete finish.

Bringing a pattern or image to life

[9]

[9]The graphic concrete used to replace 119 storm-damaged beach huts in Hampshire, England’s Milford-on-Sea, includes a whimsical pattern in keeping with the beach, as well as illustrations of actual local vistas.

By using this concrete finishing technique, the face of a precast wall can be viewed as a blank canvas onto which any image or pattern can be placed. While the maximum dimensions of most precast wall panels are about 3.5 x 14 m (11.5 x 46 ft), any number of walls can be placed side-by-side to form a larger wall—and a larger canvas for the image.

Examples of applications include a photograph; geometric pattern or texture; single word or group of words; or random placement of words or images that evoke the building’s function, site, or setting.

Photographs can be scanned and digitally ‘rasterized’ for transfer onto the retarder sheet. These images can be literal (e.g. a portrait or environmental scene) or abstract. (One architect provided crumpled paper, which was scanned and turned into a photo-realistic surface.)

Patterns may be highly repetitive, with dozens or hundreds of identical panels forming the wall of a building. Patterns may be repeated on every panel, or there may be patterns that repeat across several panels; the panels are fitted together to form relatively larger and fewer repeating patterns. Or, there may be a single, unique image or word covering a large portion of the wall, which consists of numerous panels that are assembled like a puzzle.

Wherever possible, the precast form will be used multiple times to realize efficiencies of scale. Each panel will require its own retarder membrane; however, use of identical membranes will result in a lower cost than those that differ from panel to panel. With design support from the manufacturer, the precaster can determine an ideal panel size and layout for cost and production efficiency.

Applications abound

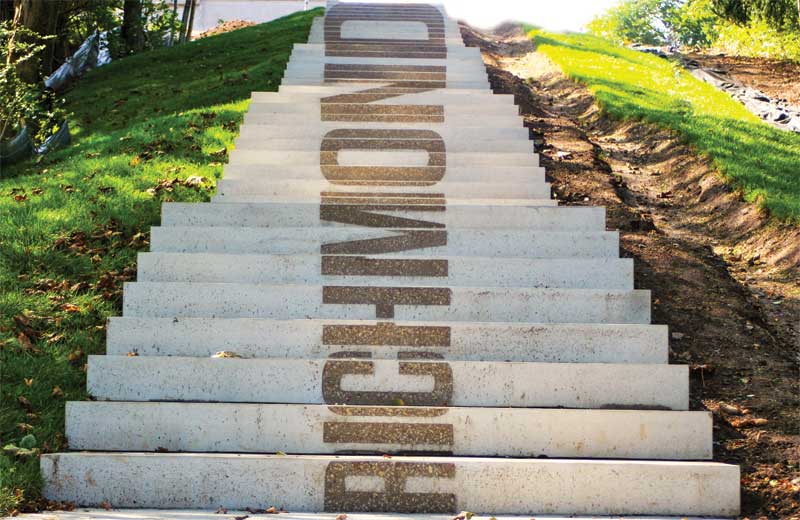

The esthetic versatility of the technology has led to a wide assortment of applications. For instance, Halifax’s Fort Needham Memorial Park provides an example of the use of a single word and evidence this technology is not limited to buildings. A set of stairs, produced by Strescon Ltd., leads from Union Street up to the memorial. Visible from the street is the word ‘Richmond,’ turned on its side and running up the stair risers. Not only does it commemorate the historic Richmond Street right-of-way, but also it attracts visitors to the memorial, in a sense inviting them to ascend.

[10]

[10]Even very utilitarian spaces can be uplifted with the use of graphic concrete. Though it may seem a contradiction, Falu Travel Centre in Sweden’s Delarna Province accomplishes just that.

When Milford-on-Sea in Hampshire, England, replaced 119 severely storm-damaged beach huts, it was concrete’s durability that attracted the designers; yet it was imperative the huts should reflect their particular location. The beach has views of the Needles of the Isle of Wight and numerous ecological wonders that Snug Architects sought to emphasize, so the graphic concrete of the huts includes a whimsical pattern in keeping with the beach, as well as illustrations of actual local vistas.

This method of finishing concrete has the potential to express not only what is, but also what can be. For example, architect Roland Carta of Carta Associates Architects Agency was asked to design Les Docks Libres, in Marseille, France. This building project consisted of 190 social housing units, 231 student rooms, and more than 250 apartments, combined with close to 5500 m2 (59,201 sf) of office and retail spaces, plus spaces for local artisans. The challenging location was slated for urban renewal; however, this Mediterranean port city has a long and treasured history. Therefore, the design features a fresco with symbols of the city’s 2600-year history, yet leaves no doubt that it is a modern building in a place ready to meet the future.

Even very utilitarian spaces can be uplifted with the use of graphic concrete. Though it may seem a contradiction, Falu Travel Centre in Sweden’s Delarna Province accomplishes just that. The bus and train station features Aalborg White cement to withstand the incredible amount of wear inside the facility. Hans Pettersson from Sweco Architects also wanted to reflect the municipality’s graphic design history. Accordingly, Modhir Ahmed’s free graphic interpretations of Falun as a world heritage site, an additional three photographs taken by photographer Olle Norling of Falun’s United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) world heritage site buildings and three photos from the world heritage listing are represented in graphic concrete. The city is said to be considering holding art exhibits in the space, too.

Getting started

Due to the vast array of possibilities and production requirements, it is important to contact a skilled precaster early in the design process. It is essential to inquire about certification, which in most cases is completed through the Canadian Precast Prestressed Concrete Institute (CPCI) or the Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute (PCI) in the U.S., to ensure best practices, quality standards, and the most up-to-date production methods.

Precasters will work with the client on the mix of cement and aggregate, as well as the esthetic, pattern, or other messaging that is desired. Due to the logistics of transporting the panels, precasters within 800 km (500) are preferred over more distant facilities.

Once a design is selected, it will be vetted by the precaster’s engineers to ensure it will meet project goals and to estimate costs. Precast concrete lead times vary according to the production schedule at each facility. Depending on the size and complexity of the project, two to three months are typical though lead times can be longer in demanding construction markets.

Graphic concrete’s permanence sets it apart from most other forms of traditional signage. Yet, in many ways, the permanence itself is message that roots the structure in its geography, heritage, and purpose.

John Carson is executive director of AltusGroup Inc., a partnership of 19 North American precast companies dedicated to precast innovation powered by collaboration. A graduate of North Carolina State University, he has more than 35 years of technical business development and strategic marketing experience. He can be reached via e-mail at executivedirector@altusprecast.com[11].

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/NeedhamStairRisers_StresconLimited.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/La_ngbrodalsskolan_3.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Fredriksen_La_ngbrodalsskolan_v2-3.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Graphic-Concrete-Process-by-Jacia-Phillips-5276.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Graphic-Concrete-Process-by-Jacia-Phillips-5345.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Graphic-Concrete-Process-by-Jacia-Phillips-5170.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Graphic-Concrete-Process-by-Jacia-Phillips-5252.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/J1A9817.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Milford-on-Sea_9.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Bussdepa_Falun_GCArt_Design_SE_300dpi_001.jpg

- executivedirector@altusprecast.com: mailto:executivedirector@altusprecast.com

Source URL: https://www.signmedia.ca/graphically-imaged-precast-concrete/

[4]

[4] [5]

[5] [6]

[6] [7]

[7] [8]

[8]