Illuminated Signs: Common issues in permitting LED displays

by all | 31 October 2016 10:00 am

Photos courtesy Daktronics

By Roger Brown

Regulatory issues have often posed a barrier to the sale of large-scale outdoor light-emitting diode (LED) displays. In some cases, they have faced moratoriums or outright bans. In others, sign shops and their clients have at least encountered difficulty acquiring permits.

The best way to address the challenges that have become common in the permitting of large LED-based digital signs—both in terms of helping sign shops get permits and of encouraging governments to adopt appropriate regulations that balance the public’s esthetic concerns with the business community’s need to capture attention with signage—is through education. Many complaints about propositions for outdoor LED displays are a matter of comparing apples to oranges, such as when citizens in a small town complain, “We don’t want to look like Las Vegas!” Officials in different jurisdictions need to understand exactly what businesses and sign shops are actually asking for.

Similarly, when an existing sign is too bright and/or animated for its location, it hurts the entire sign industry, because locals will fight any further attempts to put up electronic message centres (EMCs) in the future. It is very important to improve the reputation of the sign industry by highlighting appropriate esthetics and showing how LED displays can be not negative additions, but rather positive assets, to their communities.

This process of education will be a matter of addressing some of the most common issues that have been raised in opposition, including sign brightness, message hold times and transitions, display areas and safety concerns.

Brightness

The most common concern expressed about EMCs and other large digital signage is brightness. Some signs are not dimmed properly at night, for example, which not only bothers people nearby, but can also result in higher-than-necessary power bills for the client, while making text less readable and thus less effective at accomplishing the sign’s purpose.

With this in mind, it is important to sign shops, their clients and the public for appropriate levels of brightness to be maintained throughout day and night. In response to the issue, the sign industry has collectively developed technical standards and suggested them as a regulatory framework for jurisdictions.

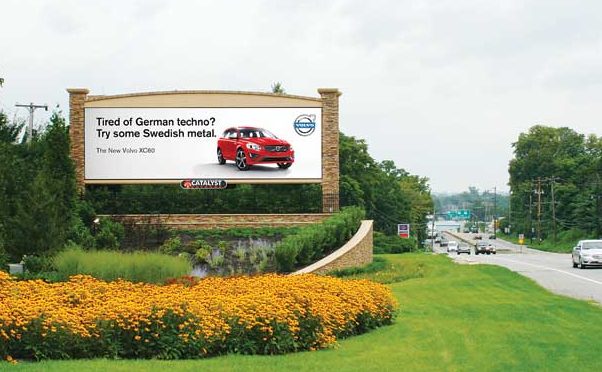

Most outdoor LED displays are nowhere near the scale of those in Las Vegas, Nev., as citizens tend to fear.

It is hoped this effort at consistency will help avoid the problem of officials being sent out to make permit-related decisions on the fly (e.g. “I like this sign, but I don’t like that sign). Rather, an objective, repeatable standard could be tested in the field with technical equipment. Such standards, promoted by organizations like the Sign Association of Canada (SAC) and the International Sign Association (ISA), have been a great gift to the industry, as many brightness concerns have gone to the wayside. ISA’s EMC brightness guide, by way of example, was last updated in August 2016 and is based on peer-reviewed research by Ian Lewin, whose company—Lighting Sciences—specialized in lighting testing and was acquired by Underwriters Laboratories (UL) several years ago. SAC has also published a book about EMCs for its members.

There are two parts to illuminance standards that have been put forward in this context. The first is a requirement for any permitted EMCs or digital billboards to have automatic dimming capabilities in direct correlation with ambient lighting conditions during the course of the day and the night. This means no one has to go to the sign and manually change its brightness at different times.

The second part of an illuminance standard, which affects the degree of dimming, recommends the maximum brightness of a sign to be limited to 0.3 footcandles (fc) of illuminance above ambient light levels, when measured at an appropriate viewing distance. This is the response to the aforementioned situation where an enforcement official in the field takes a measurement of a given sign’s brightness.

While LED billboards use the same technology as large-scale scoreboards, one of the reasons they appear so different is they are subject to bylaws.

There are two ways to measure light with regard to the regulation of signage brightness. Illuminance refers to the amount of light that strikes an object at a given distance. It is used by photographers, for example, to test how much light is reaching their subject at a certain location.

The unit of measurement for illuminance is so named because it represents the amount of light seen emitting from a candle 0.3 m (1 ft) away. This is an excellent metric for measuring light from an outdoor sign, as it reflects the perception of how bright the sign is with regard to its surroundings. Also, the larger the sign, the farther away the viewer stands to measure its brightness.

Ambient light plays a significant role in how sign brightness is perceived. Indeed, signs need to be set at different light levels depending on their surroundings to achieve the same perceived brightness as each other.

The second way to measure light is luminance, which refers to the amount or density of light emitted from an illuminated object, such as an EMC. Calculated in nits and measured with a spectrometer, luminance does not take into account the need for adjustments based on ambient light, nor does it measure appearance. As a result, it is difficult for jurisdictions to use luminance for any of their regulatory activities.

So, while the sign industry has used luminance as a way to express how bright its products are, illuminance standards are recommended instead for regulatory purposes, as they make it easier for officials to take measurements and enforce regulations in the field.

Brightness can be automatically adjusted in response to ambient lighting conditions.

With regard to automatic dimming, a sign might shine at 8,000 to 10,000 nits by day, for example, and then be reduced to only 300 nits at night, all while operating within the recommended standard for illuminance. It would also not be useful to schedule a sign to dim each evening at 6 p.m., since dusk and dawn come at different times throughout the year. Thus, it is better to use light-sensitive photo cells for automatic dimming, so the sign responds to ambient conditions as they change.

Hold times and transitions

‘Hold time’ refers to how long a message remains fixed in place before the sign transitions to another message. The shorter the hold time, the more beneficial the sign can be to its owner, as it can display a larger number of paid ads, in the case of a digital billboard, or convey more details about a business, in the case of an on-premise EMC.

In most jurisdictions today, hold times and transitions are regulated by local bylaws, which also restrict movement so as to prevent the display of full-motion video and animation. Instead, LED-based billboards are usually only allowed to show a series of static images, each for a certain amount of time.

Merit Construction’s sign in Edmonton is an example of how an LED board allows more details about a facility to be displayed.

A hold time of eight seconds is fairly standard for digital billboards. If a hold time of two to three seconds were allowed, then the same type of sign could instead showcase a greater number of simpler messages.

Regulations also cover message transitions in an effort to restrict the display of animated effects. In many cases, no transition effects are allowed, even though short ‘fade’ effects could help soften the shift from one message to the next.

In early 2015, the Transportation Association of Canada (TAC) released guidelines with added recommended restrictions for transitions and other movements on digital and projected advertising displays (DPADs). The guidelines are very conservative and have raised an uproar in the sign industry, as they could have an adverse effect on digital signage if they are applied by Canadian municipalities. While TAC admits no studies have demonstrated digital signs increase traffic accidents, for example, the report is nevertheless based on the premise that DPADs are designed to distract and should be required to emulate static signage.

Display areas

Cities have addressed the issue of LED display area in different ways. Some bylaws place no particular size restrictions on EMCs beyond those already affecting other types of signs. In many cases, however, they are regulated based on set sizes—i.e. square footages—or as a percentage of the total area of a sign’s overall face, so as to prevent the appearance of a ‘black box on a stick.’ This comes from a desire for sign structures to be esthetically pleasing.

Safety concerns

EMCs have been studied for more than 30 years and never been found to be hazardous to the public’s safety. People assume they must pose a danger by distracting drivers, but this is faulty logic.

Statistical studies that have counted accidents along a roadway before and after the installation of an adjacent LED display have always shown no increase in their numbers. The more difficult problem, however, arises when driver distraction is measured in ‘human factors’ studies, which involve mounting a camera in a car to map out where the driver glances while on the road. These studies show that drivers are indeed ‘distracted’ by signs in that they look at them, but the key finding is they don’t glance at digital signs for any longer or any more frequently than is already acceptable to traffic safety researchers.

In some jurisdictions, LED displays are regulated as a percentage of the total area of the sign, so as to prevent the appearance of a ‘black box on a stick.’

To wit, the average driver’s glance at an EMC lasts approximately half a second, which is far lower than accepted thresholds for traffic safety concerns. The basic standard suggests a glance of more than two seconds would be needed to increase the possibility of a traffic accident. Texting while driving, for example, represents a distraction of four to six seconds, which is why there are increasing regulations against such behaviour.

In other words, signs do distract drivers, but distraction is something that can be measured—and the level of distraction caused by signs is not dangerous.

In the real world

Beyond these issues, there may be further distinctions made in regulations based on zoning districts, e.g. downtown versus general commercial versus highway commercial. There is no need for a ‘one size fits all’ rule anyway. A jurisdiction can allow signs where they are useful and restrict them elsewhere. The technology of an LED display, for example, may make it inappropriate for installation in a historical area of a town.

Seeing the real-world implications of these signs usually helps balance everyone’s needs, but the process can take quite a bit of educational outreach first. The more comfortable and familiar authorities become with LED displays, the more appropriately they will regulate them.

Roger Brown is a signage legislation expert with Daktronics, which engineers scoreboards, EMCs and other large-scale LED displays. This article is based on a seminar he presented earlier this year on behalf of the Sign Association of Canada (SAC). For more information, visit www.daktronics.com[1] and www.sac-ace.ca[2].

- www.daktronics.com: http://www.daktronics.com

- www.sac-ace.ca: http://www.sac-ace.ca

Source URL: https://www.signmedia.ca/illuminated-signs-common-issues-in-permitting-led-displays/