LED displays: The basics of binning

by | 9 December 2020 2:37 pm

By Robert Simms

[1]

[1]Though the diodes within a light-emitting diode (LED) display can seem identical to the naked eye, every diode is not made equal, and one inconsistent diode can compromise an entire display.

If a display manufacturer were to indiscriminately purchase a run of packaged diodes from a diode manufacturer without giving any thought to the variation in optical and electrical specifications between the diodes, the display product they eventually manufactured would exhibit inconsistent performance. To avoid the outsized impact on performance differences between diodes, manufacturers, at the request of display manufacturers, sort newly created diodes through a classification process that groups together like diodes based on three separate metrics. Display manufacturers then purchase only those diodes that fit their parameters. This sorting process is referred to as ‘binning,’ and the metrics commonly used to ‘bin’ diodes are brightness, colour wavelength, and forward voltage.

Why do diodes differ?

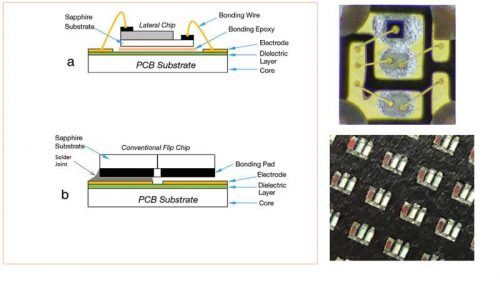

Though the diodes within a light-emitting diode (LED) display can seem identical to the naked eye, every diode is not made equal, and one inconsistent diode can compromise an entire display. Some may ask how this is possible when every diode used in a display is created using the same process. The answer to this question can be understood through a simple analogy. Imagine spraying a flat surface with spray paint, using a precise automated system that aims to coat the surface equally. Even though one may limit the number of variables and strictly control the operations of the system, they are still going to find minor inconsistencies and variations. The same is true for the diode manufacturing process. Each diode made in a production run will differ slightly from the others on its silicon wafer—even though they were all created with the same materials, ostensibly under the same conditions. Variations between diodes on separate wafers will be even more prevalent. The diode manufacturer will then pick and place the diode from these wafers into their packaging, complete the wire bonding (or wireless bonding), seal the package, and then sell these completed LEDs to display manufacturers.

[2]

[2]The diode manufacturer picks and places the diode from the wafers into their packaging, completes the wire bonding (or wireless bonding), seals the package, and then sells these completed light-emitting diodes (LEDs) to display manufacturers.

Why should diodes be binned based on luminosity, wavelength, or voltage?

Most display manufacturers will only bin based on brightness or wavelength—forward voltage is largely ignored in the binning process since it can be controlled and adjusted on its own by a display’s driver chip. Each of these measurements come with an acceptable tolerance ratio.

Approximately 90 per cent of the market will bin based solely on brightness, as measured by millicandela (mcd), since the diodes tested to be brightest at the manufacturing stage will be the most efficient diodes in the field. Unless a display looks splotchy or imbalanced, the brightness for these diodes, once they are in place, must be set to the same level. For example, a manufacturer purchasing diodes from their supplier’s highest performing bin may have to decrease 36 mcd diodes down to the level of 26.9 mcd diodes. The 25 per cent reduction in brightness from 36 to 26.9 mcd can seem steep, but it is a paltry drop when compared to the millicandela measurements of diodes from lower performing bins, which could see a diminishment of more than 50 per cent.

The segment of the display market that bins for colour wavelength is largely focused in the cinema space or professional video playback. For clients in non-cinema applications, the uniform efficiency of the diode is the most important consideration, so brightness is prioritized. In the cinema space, where brightness is less of a factor, having diodes with colour wavelengths that can accommodate standardized colour spaces becomes the higher priority. For example, if a client requires an LED display that can hit the standard colour space of Rec.709 (standardizes the format of high-definition television, having 16:9 [widescreen] aspect ratio), a bin of blue diodes with a wavelength range between 464 and 468 will deliver diodes outside of the Rec.709 standard, while a bin with a range between 462 and 466 will keep one within Rec.709.

What happens if diodes are not binned properly?

When targeting a specific colour space, improper binning can result in failure to deliver on a client’s request and a splotchy picture. When targeting maximum brightness and efficiency, improper binning will force one to drop the brightness levels across their entire display, leading to a less efficient product with worse greyscale quality. Every display will exhibit small inconsistencies over time, but negligent binning will exacerbate the issues stemming from these variations, necessitating repeated calibration. This corrective action contributes to eroded performance and decreases display lifespan.

Before completing a display product, display manufacturers perform a smoothing process called calibration. Sophisticated optical equipment gathers data on every pixel within a display, and then runs that data through analyzing software to generate a set of coefficients to apply to each diode. Once applied, these coefficients attune the performance of every diode in the display down to the levels of the worst-performing diode. This process improves the consistency of the display, but it reduces the brightness. If done incorrectly, it can result in a proportional decline in greyscale quality. As the greyscale quality erodes, minor differences between shades of the same colour begin to fade. In other words, on a calibrated display, Coca-Cola red may no longer be distinct from other reds. This can be problematic for brands that have paid large sums of money to showcase a specific colour. Although, calibration smooths overall consistency, a display should not be calibrated too often because it diminishes brightness and thus greyscale, lessening the impact of the display over time.

[3]

[3]Most display manufacturers will only bin based on brightness or wavelength—forward voltage is largely ignored in the binning process since it can be controlled and adjusted on its own by a display’s driver chip.

Does binning have any downside?

The more specific one’s binning requirements, the smaller percentage of a given manufacturing run one is purchasing. This requires a provider to perform multiple runs, which adds to the cost. This is especially true when binning for both brightness and wavelength, as the more specific one’s bin requirements get, the more production runs one requires the manufacturer to perform. Binning to hit the Rec.709 colour space can increase costs by 20 to 30 per cent, while hitting cinema quality DCI-P3 (a common red, green, blue [RGB] colour space for digital movie projection from the American film industry) can increase costs by 50 per cent or more as bins to that standard can account for less than five per cent of a total production run. These increased costs are worth paying to deliver a display product that is consistent, high performing, and long lasting. After all, a chain is only as strong as its weakest link, and a display is only as good as its worst diode.

Robert Simms is an experienced audiovisual professional with a talent for communicating highly technical subject matter in a digestible format. His writing has been featured in many industry publications during his time with NanoLumens, including Sign Media Canada, Sound & Communications, and Systems Contractor News. Simms pairs a malleable writing style and passionate research ability with a nuanced understanding of industry topics and personalities. For more information, visit www.nanolumens.com[4].

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Telstra__SydneyAustralia__33.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/FlipCHip_Vs_Lateral_Chip.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Spokane_Airport.jpg

- www.nanolumens.com: https://www.nanolumens.com/

Source URL: https://www.signmedia.ca/led-displays-the-basics-of-binning/