Planning for health-care facilities

by all | 7 February 2014 8:30 am

[1]

[1]Images courtesy GNU Group

By Philip Murphy

Health-care facilities are among the most complex environments accessed by the public. As hospitals and medical centres strive to improve efficiency and the user experience, one of the key considerations is how to successfully guide people to their destinations.

A prodigious amount of research has been conducted as to how people navigate health-care environments, including studies of the effects of user disorientation. These studies have confirmed wayfinding contributes significantly to users’ satisfaction.

Complex environments

Many factors contribute to wayfinding challenges in health-care environments. For one thing, these types of facilities are too often characterized by labyrinths of monochromatic halls and walls, with few cues—other than signs—to distinguish different uses of the space or people’s destinations. As such, the environments facing most visitors are confusing.

[2]

[2]The concept of ‘progressive disclosure’ has been used very effectively in airports, where visitors are guided incrementally to their destinations.

While contemporary design is making great strides in changing these conditions, many health-care facilities today are still a perfect setting for getting lost. Indeed, one of the top causes of patient dissatisfaction is the ease of becoming lost while navigating virtually indistinguishable corridors.

Another problem is continual change, as health-care facilities rarely remain static. Inevitable changes include the relocation of departments and architectural updates through renovations, additions or new construction. So, the environment patients encountered during their last visit may be entirely different the next time.

Further, many hospitals and clinics deliver care in a decentralized fashion. Patients often find themselves navigating multiple buildings and needing to visit numerous different offices during a single health-care campus visit. While wayfinding should logically involve linear paths, this is rarely the case.

Traditionally, the task of guiding patients, visitors and other facility users has fallen onto signs alone. While signage certainly remains a significant component of any wayfinding approach, however, a broader spectrum of tools is needed. Indeed, the entire professional discipline of environmental graphic design (EGD) has evolved to provide more effective solutions to the aforementioned problems. One such solution is integrated wayfinding.

Integrated wayfinding

Through EGD, multiple forms of communication are layered within a facility to ensure users have all of the information they need to get to their destinations easily and on time. The concept of integrated wayfinding is to consider the many ways users can receive such information, including but not limited to signs, and then to respond by distributing the information when and where it is needed.

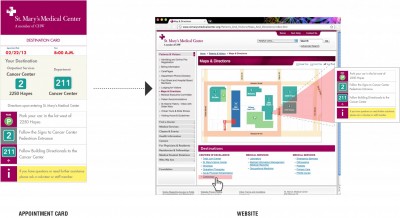

Some hospitals attempt to provide an ideal patient experience from the beginning with an appointment reminder card that includes some of the same information found on signs, such as simple maps, parking instructions, entry points and departmental icons. Their websites often provide the same orientation details, while smart phone and tablet computer applications are also entering the mix of wayfinding tools.

[3]

[3]Some hospitals integrate wayfinding sign information into their appointment reminder cards and websites. Smart phone and tablet computer applications are now also entering the mix.

Hospital employees commit inordinate time to helping people find their way. While this is one of the problems that integrated wayfinding should solve, there will always be some need for interpersonal communications in the mix, whether formally structured—as through phone outreach and information desks—or through direct encounters whenever visitors seek guidance.

In line with EGD, architecture and interior design can provide powerful orientation cues. In new facilities, there is an enormous opportunity for floor plans and the relationship between various rooms and departments to support wayfinding. The colours, materials, graphics and other visual cues implemented through interior design or renovations can help clearly designate different floors, zones and departments.

Simpler signage

Even with such a wayfinding mix, signs will remain the single most pervasive way to provide directions in health-care environments.

When a patient arrives at the facility, especially, signs become the most important guide for their journey, from start to finish. Unfortunately, in an attempt to provide all of the information a visitor needs, most health-care facilities’ signs are too crowded with details and often provide them at the wrong locations. When directions are offered to virtually any place a patient might need to go, too early in his/her journey, they only add to the confusion.

One alternative concept is ‘progressive disclosure,’ i.e. providing only the information needed to direct the patient to the next decision point. This concept is already used very effectively in large airports, where visitors are guided in increments—first to the correct parking lot, then to the terminal, then to the concourse and finally to the gate.

In most health-care environments, progressive disclosure requires rethinking the way destinations are identified. Alphanumeric designations might be used to label departments or buildings, rather than specific names and functions. Then, as patients get closer to their destinations, additional alphanumeric can be provided to designate floors and rooms.

This concept has largely been ignored in the design of health-care facilities because they are not organized linearly like airports, but it can nevertheless become a fundamental component in planning and help simplify communications. By requiring fewer instructions to be viewed on each sign and remembered, more space opens up on those signs for larger type, meaning greater legibility.

[4]

[4]Many health-care facilities have requirements for signs to comply with local codes, ordinances and life-safety regulations.

Designing a sign system

For a health-care signage system to function effectively, a number of orientation issues must be clear, including paths of travel, preferred routes, the designation of destinations, common language and the hierarchy of sign types within the system. All of these factors need to be considered before planning how directions will be given.

Common language

The language of health care can be confusing. ‘Ophthalmology’ and most other medical terms have little meaning to most people, so when they are used to designate destinations, they only create confusion. A user-friendly term like ‘eye care’ will make it much easier for visitors to know where to go.

Inconsistency of terms within a single facility can also add communications problems. If a patient is instructed to go to the X-ray, but the sign says ‘Radiology,’ uncertainty is created.

While these concerns may seem simple to address, there needs to be consensus-building among many stakeholders before a health-care organization can adopt and embrace common language. This process needs to happen before committing to the vocabulary of a sign program.

Graphic symbols can be even more common, visually representing care processes and the parts of the body being treated in a way multilingual users can all understand.

Hierarchy

A comprehensive sign system for a health-care facility may include as many as 50 different categories of signs, from outdoor monuments to room numbers. Each type needs to be designed to accommodate the necessary information in a legible way, which involves attention to scale, type size, fonts, spacing and borders appropriate to viewing distance, illumination, colour contrast and orientation of arrows.

The proper locations and placements are also important to the effectiveness of signs. Sightlines, height from the ground, orientation to paths of travel and relationship to the destination will all influence how information is presented.

[5]

[5]Wording choices for signs should be simple, clear and quick to read.

Esthetics

Signage contributes to a facility’s character and quality, complementing architecture and interior design. Visual vibrancy and playfulness in a children’s hospital may contrast with subdued elegance in a senior-care facility. The appropriate expression of form, colours, typography and materials will shape a positive experience for the visitor.

Operations

The efficacy of a sign system is an ongoing matter. While the design must accommodate the initial budget, there will also be life-cycle costs, maintenance, cleaning, repair, replacement and other practical considerations for long-term viability.

Also, as mentioned, the dynamic nature of health-care facilities means continual change. So, sign systems should be designed for efficient, cost-effective and timely updates as needed.

Given the significant costs of implementing a comprehensive program, it is imperative for hospital managers to look at wayfinding as an investment. After all, research indicates the cost of poor wayfinding can be even higher, with money wasted by missed appointments and by staff spending valuable time showing patients where to go, along with a negative impact on the facility’s reputation.

Compliance

Many health-care facilities have distinct requirements for compliance with local codes, ordinances and life-safety regulations, which are important considerations when planning and designing signs. A facility that does not meet these requirements will not get its operating permits.

Developing a program

The development of an integrated wayfinding program parallels the architectural process, including project phases for research, planning, design, documentation and implementation.

[6]

[6]Given the dynamic nature of hospitals, their sign systems should be designed to allow updates as needed.

Research and planning

Every health-care facility has its own physical requirements, organizational configuration and internal politics. As such, a wayfinding ‘task force’ should include internal and external stakeholders, to ensure continuity and consistency of directions and decisions and to avoid conflicts that could result in additional costs. This group can provide input in terms of strategy, organizational idiosyncrasies, common language and ongoing program management.

The research and planning phase includes assessing current conditions, surveying user groups, identifying paths and destinations, establishing an information hierarchy and determining the wayfinding language. Once the functional and esthetic criteria have been addressed, along with compliance and operational parameters, a wayfinding master plan should be compiled.

The master plan is a comprehensive guide for how the wayfinding program will work, from creation through implementation to ongoing management. It should provide options for fabrication and installation based on budgetary considerations.

Once every sign type is identified and the necessary quantities determined, potential high and low costs should be estimated for each type. By multiplying these costs by the number of signs, a budget range can be calculated for the entire project. Then, choices can be made about how money will be prioritized and allocated.

Design

The final sign designs will respond to the criteria in the wayfinding master plan, ensuring creative concepts can meet the functional, esthetic and budgetary goals of the program as they are brought to life.

Documentation

Beyond design, documentation includes instructions for the fabrication and installation of the signs. Large-scale, ongoing programs for organizations with multiple facilities will typically include all signage standards as part of the documentation package.

Implementation

The system’s designers can assist in identifying and choosing preferred, qualified sign fabricators and installers. The process may need to be negotiated and managed carefully to ensure quality.

[7]

[7]No matter how good a sign system is, there will always be some need for interpersonal communications to help patients find their way with confidence

As mentioned, even with the most effective wayfinding program in place, visitors will still ask for directions. So, another component of integrated wayfinding is the careful orchestration of how these directions are given. Staff should be taught to guide patients with simple, consistent instructions and the common language of the sign system.

Simple but complex

A comprehensive, integrated wayfinding program may in the end appear simple, but there is significant complexity behind its effect on the visitor experience. It demands input from and collaboration between many stakeholders. It requires an acute understanding of users’ behavioural patterns.

The results are worth the effort if visitors and patients getting lost can become a thing of the past. When wayfinding is directly integrated into facility design, rather than added as an afterthought, it can foster an intuitive environment that reduces patients’ stress and thus enhances their healing.

Philip Murphy is president and CEO of GNU Group, a design and project management firm that specializes in branding, environmental graphic design (EGD), architectural signage, wayfinding and marketing communications for real estate owners, developers, users and their consultants. For more information, visit www.gnugroup.com[8].

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/KPO-NBBJ-p4-2.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Concourse-Dir-Sign.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/appt-card.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/img_4102_retouch.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/IMG_6087_retouch.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/img_4187_retouch_2.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/iStock_000009941499Small.jpg

- www.gnugroup.com: http://www.gnugroup.com

Source URL: https://www.signmedia.ca/planning-for-health-care-facilities/