By Peter Saunders

Sandy Baird had several careers before opening Windwalker Sign Studio in Port Colborne, Ont., where he has established a successful niche over the last five years by providing carved signs to local retailers and other businesses seeking a traditional style.

Originally hailing from nearby St. Catharines, Baird studied technical illustration at Mohawk College in Hamilton, graphic design at Sir Sandford Fleming College in Peterborough, Ont., and printmaking and airbrushing at the Haliburton School of the Arts in Haliburton, Ont. He also learned traditional native silversmithing from Elwood Greene of Six Nations of the Grand River, the largest First Nation band in Canada.

Baird went on to lecture on native culture at a variety of colleges starting in 1970. His career in this field included full-time work at both Sir Sandford Fleming College and Georgian College in Barrie, Ont.

Racing into signmaking

Baird first approached the sign industry in the early 1980s, when he was teaching and, in his free time, racing Formula Vee cars.

“I was always looking for help lettering the cars with vinyl,” he explains, “so I began hand-cutting the letters and logos myself.”

He learned more of his craft in a sign shop in Cobourg, Ont., where the owner taught him over the course of a year.

“I picked up an inexpensive Roland vinyl cutter and started making window signs,” he says.

His background in technical illustration and three- dimensional (3-D) design helped him, as he could visualize objects drawn in blueprints from different angles and then translate flat graphics into 3-D formats, using isometric drawings to render accurate perspectives. He began to feel limited, however, working with flat materials.

“Computer numerical control (CNC) routers were just starting to come out at that time,” he says. “They performed like a very fast and accurate jigsaw. I decided that was the next tool I needed.”

Baird also favoured CNC technology and dimensional signs because he found the vinyl cutting market had become too crowded, with many shops undercutting each other.

“I taught myself CNC routing, as there weren’t many sign shops that had the machines back then where I could learn,” he explains.

Going out on his own, he converted an old church in Terra Nova—near Creemore, Ont.—into a home and worked on signs in the carriage house workshop behind it. He bought an Axyz router manufactured in Burlington, Ont., in 2003.

Baird made signs for clients in Creemore, where his fellow signmaker and friend Shane Durnford had already found success with dimensional signs, and other nearby towns like Alliston, where a rebate program rewarded local businesses for commissioning traditional signs. His business took off and, in 2009, he moved to Port Colborne on the north shore of Lake Erie.

Starting the studio

A city of about 18,000 people in the Niagara Region, Port Colborne has seen especially strong community support for traditional downtown streetscapes, like those made famous in Niagara-on-the-Lake’s tourism district. Port Colborne’s municipal government offers a rebate to local businesses, much like Alliston’s, covering half of the cost of a traditional sign.

“When I looked at moving back to the Niagara Peninsula,” says Baird, “I noticed Port Colborne was a small city with a sign rebate program in place, but no one was making these types of signs there yet. It seemed like a good, central location from which to further develop my portfolio.”

Indeed, he was successful and quickly established a niche market for his carved signs.

“My first sign installed here got other clients interested in my work, because they had seen nothing like it before,” he says. “Ever since then, I haven’t really had to advertise. I just carry a portfolio album around with me and I benefit from a lot of word-of-mouth. The signs do the talking!”

There also wasn’t much competition for clients.

“There was one established other sign shop in town, but they do digitally printed and large backlit graphics,” Baird explains. “I met with the owner and we maintain a very good relationship. We have done a number of joint projects over the years.”

Baird had originally operated his business as Graphics on the Fly, featuring a huge, backlit housefly on his own sign. It proved a confusing brand and he changed it to Windwalker just one month later.

“I also added the word ‘studio’ to the business name when I moved to Port Colborne,” he says, “so my customers understand this business has just one artist doing everything.”

The studio operates in a downtown space built in 1948 for cold storage and adapted over the years into an electrician’s shop, an antique store, a plumber’s office and a thrift shop.

“It’s made of concrete block and it feels a bit industrial, like a very long garage,” says Baird. “It’s not pretty and I haven’t changed it much yet, but I will set up a gallery in the front area this winter, which will allow me to show off my work and the tools I use. I’ll put up about a dozen samples, so people can check how they look and feel up close.”

He also plans to start work this spring on a full mural with native-culture students at Mohawk College and art students at Sheridan College in Oakville, Ont.

The sign shop also includes Baird’s living space.

“My commute is all of 15 steps,” he laughs. “I’ve got the Welland Canal right behind me and I can just walk down the street to buy my groceries.”

Finding inspiration

While Port Colborne’s downtown area is busier than rural Terra Nova, the backdrop of the canal, which connects Lakes Ontario and Erie, and the nautical sensibility of the city have helped provide inspiration for Windwalker projects, such as a new sign featuring a life-sized dimensional mermaid.

“Back when I was learning silversmithing,” Baird says, “my teacher told me to go outside whenever things stopped working creatively, walk around until my head cleared and then come back when I could put my best into the work. There’s a similarity in the energy I put into dimensional signs today. I try to add humour and spirituality to my work.”

With this focus on creativity, every project is highly customized for its owner.

“I spend a lot of time talking with my clients before starting to work on their signs,” he says. “Many of them are starting a small business and a sign is their first chance to make a good impression. They can tell I’m excited, too. I work with them to find the best style, colours and fonts to represent their business. You want to give customers the right feeling before they walk in the door.”

As Baird works alone, without any colleagues to bounce ideas off of, he must also rely heavily on himself for inspiration.

“Fresh ideas can come from many places,” he says. “A lot of my signs first come to me in dreams, where I see them fully developed. I also use music a lot in my work. I’ll ask my clients what their favourite song is and then put that on when I’m working on their sign. It helps set the pace for what I’m doing. And it helps energize me to keep going on those nights when I’m up until 3 a.m.”

The only time Baird does not work alone is when he accepts an art student as an intern each year.

“The shop gives them a taste of the industry and lets them see an outlet for their artistic talents,” he says. “The internships also fit with my background in teaching. I get to turn my studio into a training facility. I love to pass these skills along and see the creative spark in the next generation.”

The benefit of Extira, commonly used as exterior sheeting for houses, is Windwalker’s signs stand up well to the elements.

Built to last

Almost all Windwalker signs are carved using Extira, a treated exterior composite panel building material designed to resist moisture and rotting, and then coated with Benjamin Moore water-based paints.

“Few signmakers use Extira, which surprises me,” Baird says. “It’s most commonly sourced as exterior sheeting for houses. It carves well, takes paint well and is cheaper than signfoam, but the most important aspect is its longevity. I tend to overbuild the strength of each sign, since I don’t want them to fail. You can take a baseball bat to them and they’ll hold up. So, I can deliver without worrying about callbacks due to product failure.”

By way of example, his first carved sign, which he made in Terra Nova in 2003 for the Baroque Pearl Lingerie Boutique in Alliston, is still displayed there today.

“Some of my old signs have come back to roost, but only because those clients retired,” he says.

Most of Baird’s new clients are retailers, with about half just starting out and the other half rebranding their existing shops.

“My next step will be to court wineries and other larger-scale clients across the peninsula,” he says. “There isn’t much turnover or repeat business with these types of signs—they’ll probably outlive me— so I always have to find new business. Fortunately, I get very good referrals.”

Beyond his artistry and choice of materials, Baird credits much of his success to his sheer tenacity.

“Back when I was racing, one of my competitors saw all the ads on my car and wondered how I got so many sponsors, especially when I never won any races,” he says. “I never give up! I love what I do and I live for the challenge of the next sign.”

Shaping a Sample Sign

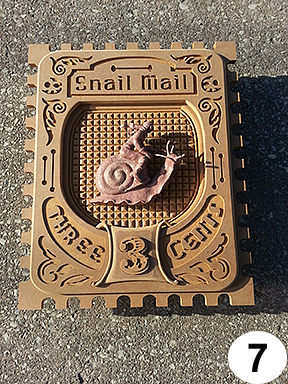

After designing a concept in Corel Draw for a new 559 x 737-mm (22 x 29-in.) sample sign for his front gallery, Baird sends the file through bridge software to generate code for his Axyz computer numerical control (CNC) router.

Baird also shapes elements of the sign by hand, using chisels, files and sandpaper. As the composite panel has no grain to fight against, the work goes relatively quickly.

After shaping the number three, Baird checks he has left the right allowance for primer and paint. All areas, whether machined or worked by hand, are sanded smooth, then primed.

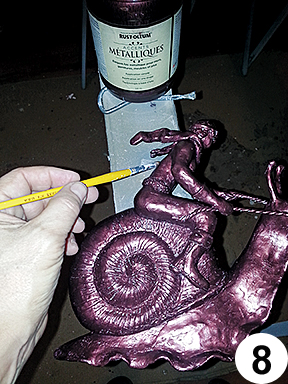

The snail is created using high-density sign foam as a base silhouette and then applying and shaping clay by hand.

The snail is paired up with its rider. Baird continues to add and shape clay to create finer details. As the sign will be displayed inside his gallery, no outdoors, and will not be handled by clients, he does not use Magic Sculpt two-part epoxy like he normally would.

All of the pieces are dry-fitted together to check the overall layout before moving on to priming and painting.

All of the wood-composite pieces are primed, scuff-sanded, primed again and given another light scuff.

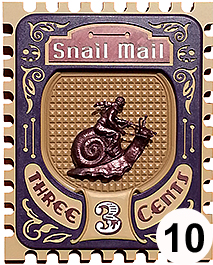

The ‘snailmail’ sign is finished using water-based, 100 per cent acrylic Benjamin Moore paints and mounted on a brick wall in the gallery.