Wayfinding: The growth of accessibility signage in Canada

By Mike Santos

While there has been relatively little action taken in Canada in recent years with regard to disability codes affecting signage at either the federal or provincial levels, a specialized industry has nonetheless emerged, with sign fabricators developing best practices based on both Canadian standards and the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) from the U.S., which affects room identification (ID) and wayfinding signage.

AODA

In Ontario, the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) was passed in 2005 to address the need to remove barriers for the disabled in built environments. Under AODA, a formal sign standard was proposed in 2010 and adopted in June 2011, with the goal of making the province fully accessible by 2025. This standard is a simplified version of sections of the International Building Code (IBC). Many sign companies in Canada have used IDC and ADA to address other areas, including contrast levels and tactile letter standards.

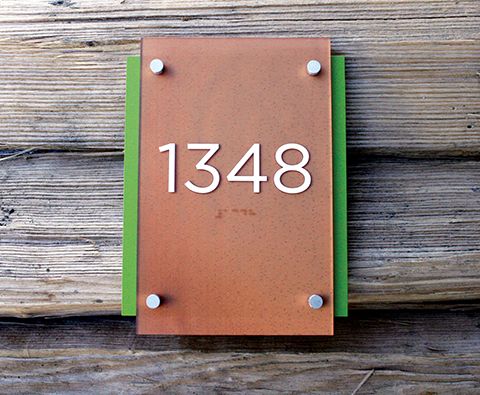

AODA requires sans serif fonts, combined upper and lower case letters, tonal contrast of at least 70 per cent, Grade 1 braille (compared to Grade 2 braille in the U.S. under ADA) and matte or glare-free surfaces.

As a code designed to serve more than one-third of the population of Canada, AODA obviously wields enormous influence, which can spill into other provinces that do not have their own codes. Some sign companies, like King Architectural Products in Bolton, Ont., have not only grown to meet AODA’s provincial demands, but have also pushed parts of the code forward—along with principles of ADA—as best practices for wayfinding systems in other provinces.

This process is similar to examples seen in the U.S., where some states developed their own additional guidelines after ADA was adopted, based on more advanced work by the International Code Council (ICC). In fact, as various states gravitated to higher standards, they became common industry practices before ADA was even adopted at the federal level.

Treasury Board and FIP

Outside of direct codes, other guidelines have had a major influence in Canada. The Treasury Board, which is responsible for regulations concerning its fellow federal government agencies, requires tactile signs in all federal government buildings, whether owned or leased. Specifically, the board’s manual says tactile signs must be used for washrooms, emergency exits, elevators, stairwells and doors off main corridors.

These requirements were adopted with the Federal Identity Program (FIP) in 1997, which was closely developed with a number of related industry associations and disability experts. FIP’s specific guidelines for signs were also based on the Canadian Standards Association’s (CSA’s) CAN/CSA B651-95, Barrier-free Design Standard, for existing buildings.

Sections of CAN/CSA-B651-95 that affect signage include requirements for sans serif characters, Arabic numerals, character width/height ratios between 3:5 and 1:1, stroke width/height ratios between 1:5 and 1:10, zero glare and minimum illumination level of 200 lm/m2 (200 lx). Tactile characters and symbols must be between 16 and 50 mm (0.6 and 2 in.) high.