Wide-format Graphics: From design to print to cut

by all | 2 May 2014 8:30 am

[1]

[1]Images courtesy Esko

By Steve Bennett

The technological landscape for the printing industry has changed dramatically over the past decade. Today, 98 per cent of all print service providers (PSPs) are using digital presses of some type. For 72 per cent, their production environments are already mostly or all digital. This has changed the nature of competition.

Rather than simply offering the same commoditized products, it is important for sign shops to add value for their customers, both before and after printing. Some 65 per cent of PSPs say it is important to offer short runs, for example, while 59 per cent say added value comes with shortened delivery times.

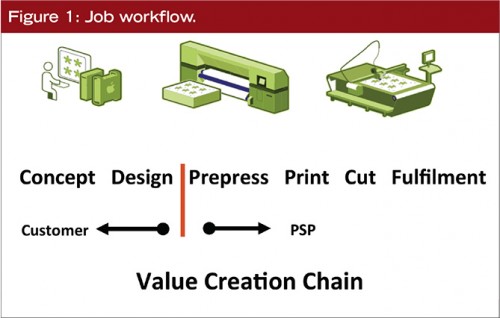

The spectrum of this ‘value creation chain’ for a complete job encompasses both customer-centric and PSP-centric elements (see Figure 1). The customer is generally concerned with a marketing concept and the design of the printed material, while the PSP is looking to add value in pre-press, printing, cutting, finishing, fulfilment and delivery.

One of the most frustrating issues for today’s wide-format graphics PSPs in this respect is how to find and resolve production bottlenecks, where output is being slowed down by specific processes, particularly during the finishing stages.

[2]Cutting options

[2]Cutting options

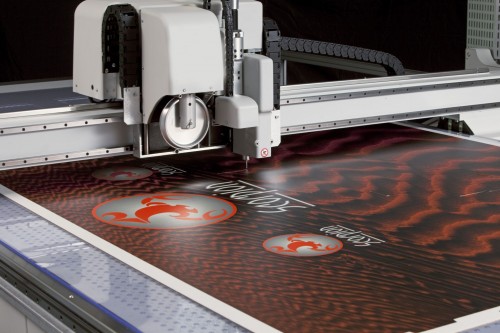

The cutting phase is typically where these bottlenecks begin. There are several methods for finishing a print job at this point.

One is cutting by hand. This is the slowest means to complete a job and, due to labour costs, often the most expensive option. With a lack of automation and consistency, manual cutting can also result in the lowest product quality.

Subcontracting is another option. It eliminates many of these problems, but can lead to some jobs taking longer than expected to complete, depending on the supplier’s priorities. The quality is usually satisfactory, but there is also less control of the work and less opportunity for profit.

A third option is to automate finishing with digital systems. This will mean high initial expenses, but most PSPs who bring digital finishing in-house report a very quick return on investment (ROI). The quality is better and more consistent than with manual cutting and, because the machines can run 24-7, bottlenecks are usually eliminated. These are all significant benefits, especially for short-run jobs.

[3]Beyond necessities

[3]Beyond necessities

In addition to avoiding bottlenecks in the finishing department, another primary reason to invest in a digital cutting system is to expand a PSP’s capabilities in terms of the shapes and dimensions that can be achieved, with a greater number of substrates. In these ways—and by considering the size of a PSP’s digitally printed output before selecting a table—digital finishing can help achieve a better ROI for a shop’s existing digital printer.

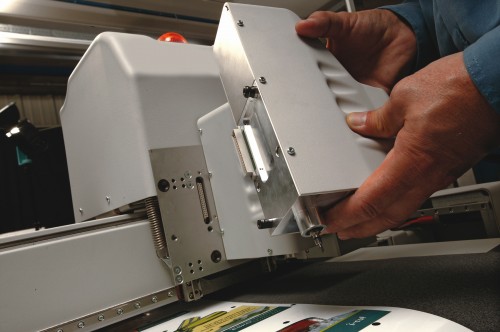

An automated finishing table can cut, rout and crease or score the substrate. Beyond these basic functions, however, it should be versatile, able to properly handle a wide range of materials—from delicate sheets to highly durable plastics, woods and metals—and offering a broad selection of finishing capabilities.

In today’s competitive market, many professionals consider speed the most important feature of a machine, but they do not always consider how efficiency depends on acceleration. It takes some time for a cutting table to ramp up to its maximum speed, but any job that requires small or contoured cuts, not just long ‘straightaways,’ will challenge a table that cannot accelerate quickly enough to its rated speed. The problem is similar to driving a massive truck around hairpin turns.

Productivity also depends on integration with the workflow, from design to printing to cutting. If the table is not a good fit for this workflow, it will be difficult or impossible to complete jobs on time.

In this regard, vision registration systems have become more prevalent. It is impossible to be completely sure a sheet of material will be manually placed on the table correctly, so the vision registration system is used to correct the die line for distortion. Otherwise, with contoured cuts, blank spaces could end up being left on the printed piece as it is finished.

Beyond ensuring a printed substrate is ‘read’ correctly, a vision recognition system can also read registration marks around every piece when materials have been ‘ganged’ together with more than one printed graphic. This ensures the cutter can compensate for pieces with distortion.

Finally, there is the issue of automation. To maximize productivity, some of today’s cutting tables can handle rolls, sheets and boards without needing an operator to manually load and unload the materials. Indeed, many cutting tables come with conveyor belts, roll feeders, sheet and board feeders and/or table extensions.

Added dimensions

Finding an appropriate cutting table is just the beginning of the process. Typical printed signs are becoming a commoditized business, with PSPs of all kinds producing them on digital presses, cutting them into rectangular shapes and shipping them around the world. Just about anyone can do that.

Without value-added features, such as colour management, these companies will compete simply on the basis of pricing and availability. If they all continue to handle the same jobs in the same way, they will end up walking into a business trap.

Similarly, while buying an automated digital cutting table can help a sign shop optimize its availability and costs by adding volume through capacity and productivity, the machine itself is not going to differentiate that shop from everyone else.

Rather, signmakers need to approach existing customers and offer greater capabilities. When clients order two-dimensional (2-D) graphics, for example, they should also be offered contoured shapes, cutting, creasing and a greater range of substrate options. These types of work will also be more creatively fulfilling to the sign shop’s in-house designers.

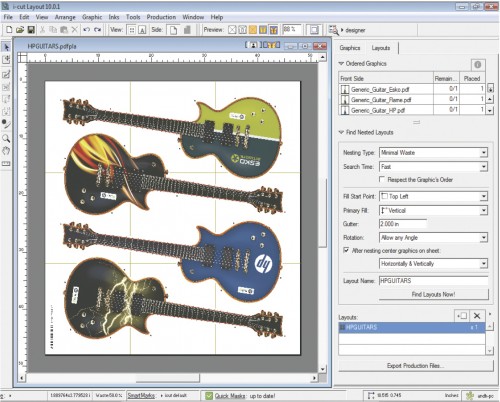

[4]

[4] [5] With true shape nesting, the configuration of graphics is optimized to reduce waste.

[5] With true shape nesting, the configuration of graphics is optimized to reduce waste.

One way to foster this creativity and value-added business is to invite customers into the shop, as early in the process as possible, and show them a range of specially created samples, to exemplify what the in-house production department is capable of handling. The key is to work with customers and guide them up the value chain, exposing them to a range of materials and applications of which they may not even have been aware.

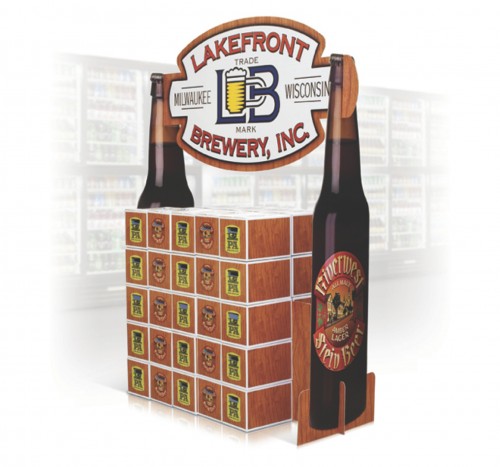

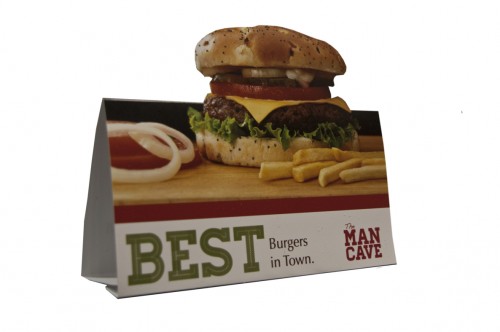

Customers who are accustomed to flat graphics should be offered three-dimensional (3-D) point-of-purchase (POP) graphics, stand-up displays and boxes for trade shows, meetings, special events and showrooms.

This will get clients’ creative juices flowing and will free them from the constraints of ‘rectangular thinking.’ Greater creativity, in turn, will lead to higher margins. Displays can be priced by the piece, rather than by the square foot.

In regard to working with customers, most structural design software suites include templates to help them visualize 3-D displays, which the PSP can help the client custom-design for finishing. Indeed, some sign shops now provide structural computer-aided design (CAD) services themselves, working with graphic designers, which helps make them more indispensable to their customers.

Pre-press bottlenecks

Even when a PSP eliminates bottlenecks in the finishing department, however, it is common for problems to persist at the pre-press stage.

Many of today’s print shops are receiving smaller jobs with quicker turnaround times. As such, the numbers of files that must be ‘cleaned up’ before going through a raster image processor (RIP) and then printed are growing significantly. This work takes time and slows down the steps after it.

Fortunately, pre-press workflow software is now being developed specifically for the wide-format graphics industry. Although such software has long been a staple of the commercial printing sector, it cannot simply be refurbished for sign shops, but must instead be reconceptualized.

Most graphics are delivered to the shop as—or can be converted to—Portable Document Format (PDF) files, so it is best for a workflow to incorporate PDF-based tools for the RIP stage. Finding errors at this stage, however, is problematic, as the time spent RIPping cannot be recouped and holds up other work. Finding errors while printing is even worse, as it means an expensive waste of labour, time and materials.

For these reasons, preflight tools are also important. They receive incoming files and determine whether or not they are ‘clean’ enough to pass along to the printer.

The shop must first create profiles that dictate its systems’ specific requirements for a clean file, but once that work is done, it becomes easier to feed PDF files into the system and make diagnostic checks. If a file has any problems, it is flagged.

Beyond flagging, a good preflight system will also let the pre-press department make edits, even extensive corrections, to the PDF file without having to send it back to the customer or to its native application.

Layout tools have also become extremely important in ensuring substrates match up after printing for the finishing phase. Otherwise, those substrates are expensive to replace.

One of the most helpful layout functions is true shape nesting, whereby the configuration of various graphics on a sheet of material is optimized so as to reduce waste. This not only saves material, but also time. The more items that can be printed on a single sheet, after all, the less time needed to complete the job, at both the printing and finishing stages.

[6]

[6] [7] Customers accustomed to flat graphics should be introduced to more creative 3-D diplays.

[7] Customers accustomed to flat graphics should be introduced to more creative 3-D diplays.

Layout also involves adding the aforementioned registration marks after jobs have been ganged, so the cutting table’s vision registration system can analyze any distortions or misaligned sheets on the flatbed. Some of today’s layout tools will automatically add a ‘bleed’ to the end of a piece, which also helps prevent leaving unsightly blank spaces if a cut is slightly off. The operator, meanwhile, can use layout tools to modify or add cutting paths, grommet holes and other special marks to assist in finishing.

Another useful function at the layout stage is including a bar code on the file. This way, when the PDF file is sent to the RIP and the corresponding cutting file is sent simultaneously to the digital finishing table, the cutter can identify each job and access the right instructions.

In all of these ways, workflow automation at the pre-press stage has become increasingly important to ensuring consistency of output, efficiency of labour and speed of processing. As numbers of files increase and customers require quick turnaround, automation can take care of repetitive tasks and eliminate bottlenecks. No matter how experienced a pre-press operator is, after all, manual work is always going to be error-prone.

Fulfilling the promise

Wide-format digital printing has certainly been a boon for the sign and display industry, but that does not mean simply purchasing a printer will lead to profitability and long-term business success. Even as digital print quality has improved by leaps and bounds, it has not been well-served by manual workflows and finishing methods that increase the risk of error and, in some cases, limit quality. Indeed, the lack of appropriate workflow and finishing systems can hinder a sign shop’s growth through bottlenecks in production.

With automated workflow at the pre-press stage and through digital finishing, sign shops can improve speed and quality, but also unleash their designers’ creativity and handle projects with higher profit margins, adding value that cannot be achieved through printing alone.

Steve Bennett is vice-president (VP) of Esko’s digital finishing business, which supplies software and hardware for the sign and display industries. For more information, visit www.esko.com[8].

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Esko_Kongsberg_XP_042.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/SM_April_2014_HR-70.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Esko_Kongsberg_i-XE10_052.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/LayoutSW.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Kongsberg-HP-Milling-Spindle2.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/LakefrontBrewery.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.signmedia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/ManCave.jpg

- www.esko.com: http://www.esko.com

Source URL: https://www.signmedia.ca/wide-format-graphics-from-design-to-print-to-cut/