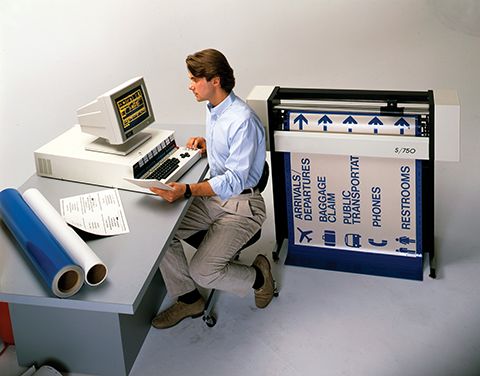

Wide-format Printing: How the sign industry was revolutionized

By David J. Gerber

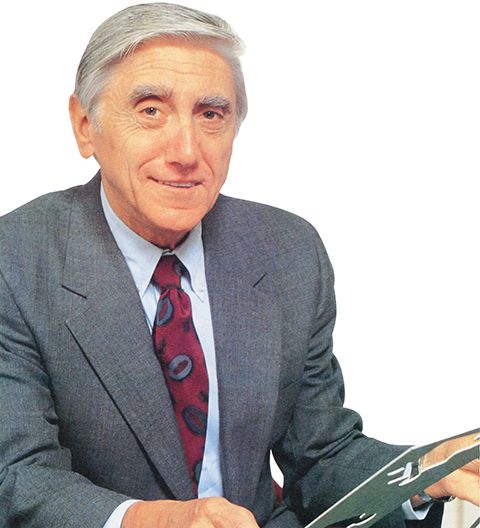

Editor’s Note: This article is based on excerpts from The Inventor’s Dilemma: The Remarkable Life of H. Joseph Gerber, a new biography by David J. Gerber about his father, who founded Gerber Scientific Products (GSP) and earned hundreds of patents for his inventions over his lifetime, ranging from the variable scale to the automated cloth cutter. His company became particularly well-known in the sign industry before he passed away in 1996.

As he exhibited when inventing the variable scale, Joe Gerber could look at an object that performed a certain function and reinterpret it as an entirely different kind of technological object. In his analysis of apparel manufacture, however, he demonstrated his inventiveness was broader than the arena of physical objects alone. By 1969, he had developed a method of invention that enabled him to recognize an opportunity conventional analysis overlooked by not considering the scope and complexity of reinventing multiple functions together. As he explained, market researchers had framed the issue of automation only in terms of “replacing a manual cutter with a computerized cutter;” they had not considered “the systems view.”

This method of inventing systems was characteristic of the ‘independent’ inventors

of the 19th and early 20th centuries, most notably Thomas Edison, who devised not only an incandescent lamp, but an entire system for lighting; his light bulb was merely one component in that system.

Like Edison, Gerber was motivated by a “drive to innovate” and he appreciated the “stimulating effect” of the interaction between components. In designing his automated cloth cutter, for example, he sought to simplify the traditional cutting path and improve accuracy, which allowed him to automate layout and sewing operations. During the 1960s, as he introduced innovations for automating the engineering of aircraft and automobiles and producing circuit boards for consumer and industrial electronics, he had come to believe in a method of creating systems as a means of realizing his aspirations.

Although he never used a personal computer (PC), Gerber rethought entire systems of design and manufacturing for the computer era. He reshaped the processes of manufacturing many of the products that influence our everyday lives: the clothes, shoes and eyeglasses we wear, the maps and signs that point our way, the books and newspapers we read and the colour TV screens and billboards we view.

Turning drawings into digital information

When Gerber began building machines in the 1950s, skilled labour and inflexible machinery represented the basis of almost all production. Computers, which until then had been used mainly to store and computer numerical data, rapidly gained such power that they could generate graphical shapes.

“The real breakthrough came in the 1960s, when we worked out how to connect a computer to a plotter, so it was possible to turn a drawing into digital information,” he later recalled.

Initially, that expertise was useful to the few organizations that needed the precision and data-manipulation ability of a computer and were willing to pay a high price; but Gerber was one of the first to foresee the industrial possibilities of the computer in design and manufacturing across many industries. The use of his computerized precision plotting in aerospace enabled the production of the first jumbo aircraft and on July 20, 1969, when Apollo 11 landed on the moon, his automated drafting machines at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas, were used for communications analysis and to display information graphically within the mission control centre.