Wide-format Printing: The hidden costs of decentralized colour management

By Bart Fret

The way digital wide-format printing has evolved is different from traditional printing. For example, traditional presses used printing plates of one sort or another, so companies would build a centralized area for both preparing their artwork and imaging the plates. This was typically referred to as the pre-press department. Then, once the plates were ready, they were mounted onto the press and the job was produced. Since every traditional press required plates, all of the work had to be routed through the centralized pre-press department.

When printing started to go digital, this situation did not change much at first. The centralized department still pre-flighted the artwork files—i.e. checked the presence and validity of all of the data needed to print them—and altered them as needed for the press. Colour management was part of this process before the files were sent to a digital platesetter.

Once digital inkjet printers began to tackle wide-format graphics, however, it became obvious two different ingredients had to be offered: (a) the actual digital printing hardware and (b) the raster image processor (RIP) software for colour and workflow management. At the beginning, RIPs offered very little colour or file management, other than pushing jobs through the press, but this was acceptable to customers. The presses were not even calibrated on a regular basis. And all the operators would do was colour-correct by turning on the RIP for each job.

As companies acquired more wide-format digital inkjet printers, the pre-press process became more decentralized, because each printer came with its own RIP. It was easy to get confused if the RIP driving a press from one vendor was different from the RIP driving one from another.

Also, as RIPs became more complex, companies that used to rely on pre-press departments to prepare files started to rely on each RIP to provide colour management for its corresponding printer. The problem with this approach is it was extremely time-consuming and costly. And while it could provide somewhat accurate colour at the time, it no longer ensures sufficient color quality and consistency to meet the demands of today’s brand owners.

Nevertheless, the approach remained common, particularly since many companies were reluctant to invest even more of their money and time into new systems. Unfortunately, this reluctance usually proved short-sighted. Research began to demonstrate the heavy costs of decentralized colour management systems, including not only measurable expenses, but also potential revenue that was being missed.

Counting costs

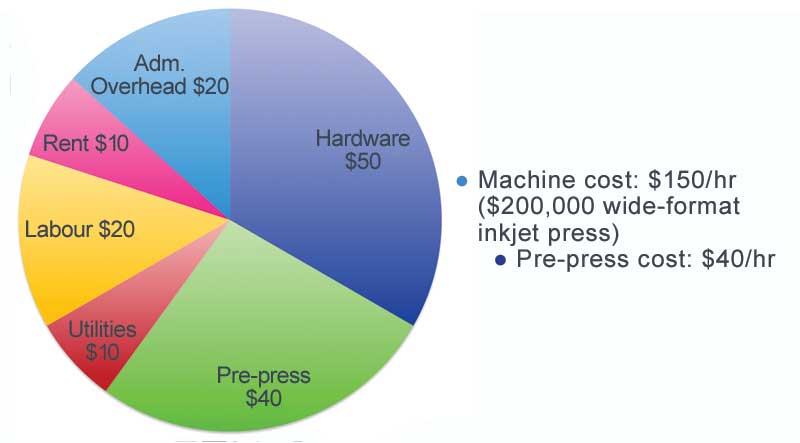

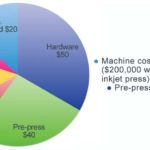

One way to consider the costs of decentralized colour management is to create an example based on rough generalizations. The cost to run a press, for example, can be estimated at $150 per hour, including not only the cost of the hardware itself, but also administrative overhead, rent, labour, utilities and pre-press work (see Figure 1).

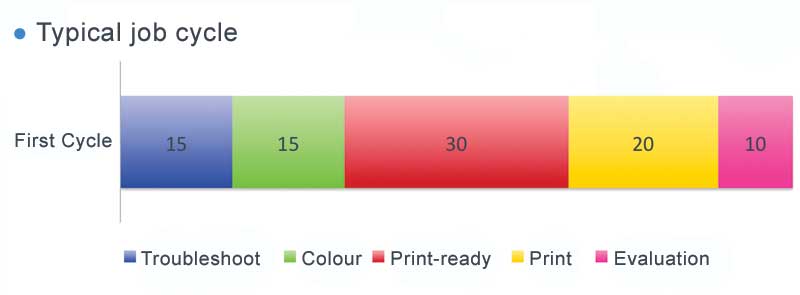

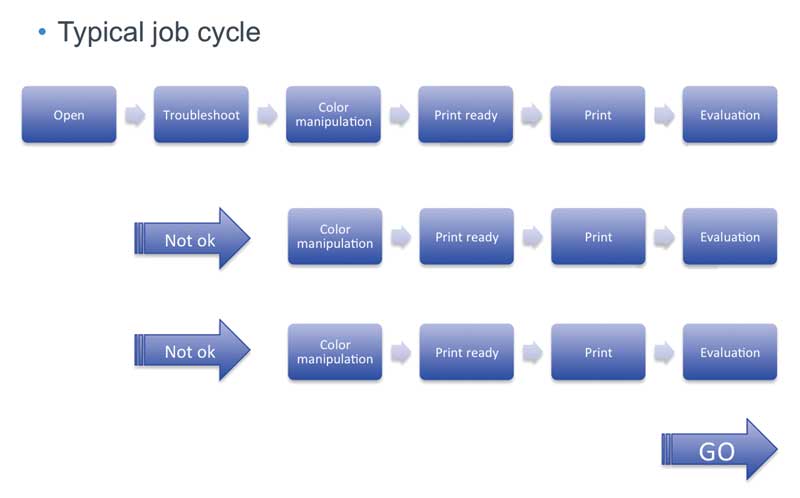

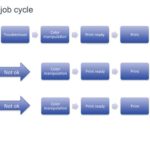

The typical wide-format printing job takes about 90 minutes. If the job is not colour-correct and therefore the printed results are not approved, however, it can take two or three cycles instead of one (see Figures 2 and 3). The first cycle only costs operator time, but each additional cycle costs additional operator and press time that cannot be recouped. And such costs could be incurred by every job, if colour is not sufficiently accurate from the start.

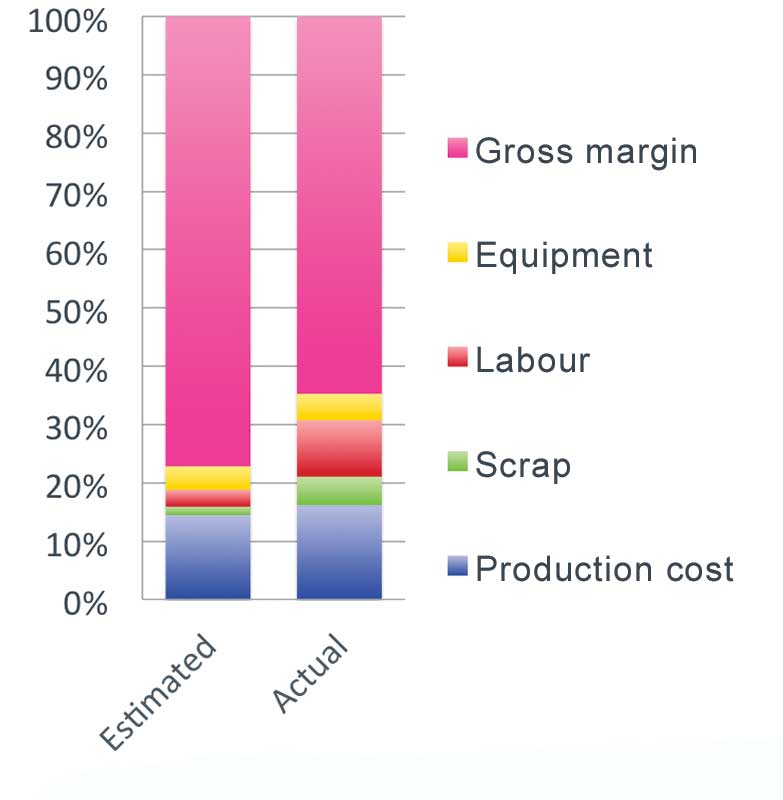

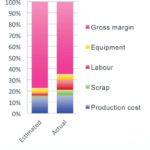

A printer’s profitability is calculated over six- or eight-hour shifts (see Figure 4). Any extra hours spent at the pre-press stage will eat away at profit margins, yet are rarely represented in job costs. And this time can leave the machines idle, reducing the company’s effective print capacity and missing out on revenue.