Wide-format Printing: The hidden costs of decentralized colour management

by all | 27 May 2016 10:10 am

Photos, charts and diagrams courtesy GMG Americas

By Bart Fret

The way digital wide-format printing has evolved is different from traditional printing. For example, traditional presses used printing plates of one sort or another, so companies would build a centralized area for both preparing their artwork and imaging the plates. This was typically referred to as the pre-press department. Then, once the plates were ready, they were mounted onto the press and the job was produced. Since every traditional press required plates, all of the work had to be routed through the centralized pre-press department.

When printing started to go digital, this situation did not change much at first. The centralized department still pre-flighted the artwork files—i.e. checked the presence and validity of all of the data needed to print them—and altered them as needed for the press. Colour management was part of this process before the files were sent to a digital platesetter.

Once digital inkjet printers began to tackle wide-format graphics, however, it became obvious two different ingredients had to be offered: (a) the actual digital printing hardware and (b) the raster image processor (RIP) software for colour and workflow management. At the beginning, RIPs offered very little colour or file management, other than pushing jobs through the press, but this was acceptable to customers. The presses were not even calibrated on a regular basis. And all the operators would do was colour-correct by turning on the RIP for each job.

As companies acquired more wide-format digital inkjet printers, the pre-press process became more decentralized, because each printer came with its own RIP. It was easy to get confused if the RIP driving a press from one vendor was different from the RIP driving one from another.

Also, as RIPs became more complex, companies that used to rely on pre-press departments to prepare files started to rely on each RIP to provide colour management for its corresponding printer. The problem with this approach is it was extremely time-consuming and costly. And while it could provide somewhat accurate colour at the time, it no longer ensures sufficient color quality and consistency to meet the demands of today’s brand owners.

Nevertheless, the approach remained common, particularly since many companies were reluctant to invest even more of their money and time into new systems. Unfortunately, this reluctance usually proved short-sighted. Research began to demonstrate the heavy costs of decentralized colour management systems, including not only measurable expenses, but also potential revenue that was being missed.

Counting costs

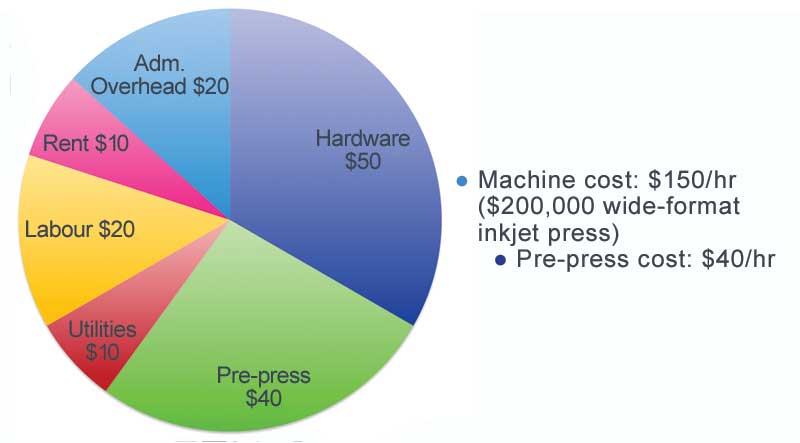

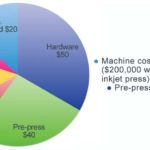

One way to consider the costs of decentralized colour management is to create an example based on rough generalizations. The cost to run a press, for example, can be estimated at $150 per hour, including not only the cost of the hardware itself, but also administrative overhead, rent, labour, utilities and pre-press work (see Figure 1).

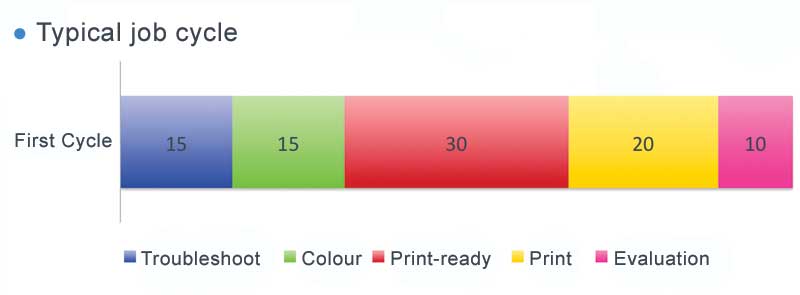

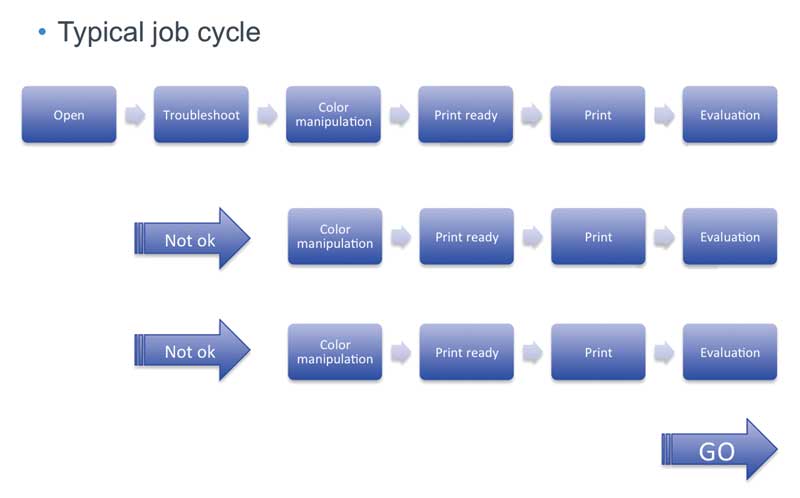

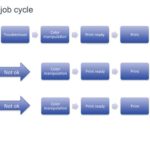

The typical wide-format printing job takes about 90 minutes. If the job is not colour-correct and therefore the printed results are not approved, however, it can take two or three cycles instead of one (see Figures 2 and 3). The first cycle only costs operator time, but each additional cycle costs additional operator and press time that cannot be recouped. And such costs could be incurred by every job, if colour is not sufficiently accurate from the start.

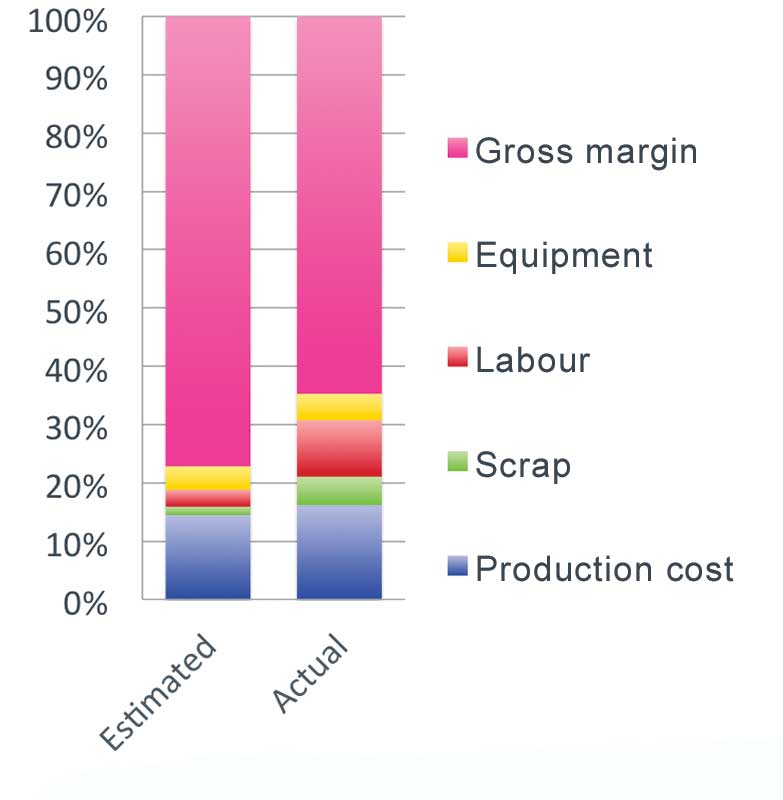

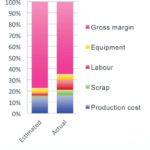

A printer’s profitability is calculated over six- or eight-hour shifts (see Figure 4). Any extra hours spent at the pre-press stage will eat away at profit margins, yet are rarely represented in job costs. And this time can leave the machines idle, reducing the company’s effective print capacity and missing out on revenue.

One reason the pre-press process became more decentralized with the advent of wide-format digital graphics is each inkjet printer came with its own RIP software.

Doubling capacity

Decentralized colour management systems can certainly generate somewhat accurate colour, but require a lot of effort to do so. They either use ‘canned’ profiles with a few colour tweaks or develop custom International Color Consortium (ICC) profiles. Colours are measured with a spectral device and various RIPs are used with their dedicated colour engines.

A centralized colour management system, on the other hand, relies on a single RIP to drive all of the digital wide-format printers in the production department. There are no canned profiles. Rather, each profile is created from scratch by the colour management system.

A centralized system can be based on proper calibrations performed to industry standards, such as the General Requirements for Applications in Commercial Offset Lithography (GRACoL). With a quality assurance program in place, regular calibrations and maintenance are performed to ensure consistent results.

In facilities that take the centralized approach, most jobs are completed in the first cycle, perhaps with an occasional second cycle for press approval purposes. As a result, the total labour costs are typically between 10 and 40 per cent of those incurred with most decentralized systems.

Indeed, a print facility freed of performing more cycles per job can typically double its throughput with the same number of staff. It takes less time to get jobs on press and then the press operators can focus on their workloads without the machines being left idle.

Improving profile creation

Among the expenses most print service providers (PSPs) never consider is the investment in time required to create profiles for each of a series of digital inkjet printers.

By way of example, one particular large-volume PSP operates a variety of flatbed and roll-to-roll (RTR) presses, including seven identical RTR models. Using a decentralized, RIP-based colour management system, it took a minimum of three hours to create an ICC profile for each of those seven digital presses, even though they were identical, for a total of 21 hours per substrate. And doing so was necessary not only each time one of the existing printers was replaced, but even each time a single new printhead was installed in one of them.

Today, with a new, centralized system, it only takes about 90 minutes to create a baseline profile on one of the printers, at which point it is automatically shared among all seven identical presses. The company does recalibrate and linearize the performance of the printers to ensure they produce identical results, but this process takes less than half as much time as creating a new profile. Whenever a printer or printhead is replaced, it takes less than 40 minutes per substrate to match the new device to the others. And the results are more accurate than before.

Indeed, the process of colour matching has improved. Whenever the company matches a Pantone colour on one of the printers, the software shares the data with the other six.

The recalibration process is highly valuable. If a colour was tweaked in one of the seven identical printers six months ago, for example, but now one of those presses has drifted, then once the company recalibrates that machine, any previous colours in its library are also adjusted to perform just as before. In the past, on the other hand, colours would drift so far from their targets and linearization was so far off the mark, the only answer in most cases was to spend time building new profiles.

With the previous system, about 15 per cent of files to be processed required colour corrections. Usually, these corrections took three to five cycles. On average, it would take two to four hours before actual print production could start. The machines generally sat idle for one to three hours.

Now, thanks to centralized colour management, the company has reduced the need to retouch files by 90 per cent. The few jobs that still require some colour corrections usually only need one to two cycles. The presses rarely stand still.

Beyond the economic advantages of saving time and labour, the company can now print jobs across different machines with greater certainty the colours will match. Jobs requiring multiple printers and substrates—which comprise much of the company’s work—are now easier than before.

There used to be occasions where one printer would need to be isolated to produce an entire job by itself. Now, the company is so much more comfortable with its colour management efforts, it can instead spread one job across all seven identical presses.

Automation is highly beneficial. Since the installation of the centralized system, the company has increased its sales by 100 to 200 per cent, while only increasing staffing by 20 per cent.

Measurement devices should be used to ensure colour accuracy throughout the design and printing process.

Boosting profit margins

Another company that ran into similar issues was a midsized PSP that used flatbed printers, digital presses and an industrial cutting table to produce graphics and packaging. Before it invested specifically in colour management technology, it simply created ICC profiles using the printers’ RIP software. Unfortunately, this process often took four to five cycles before the colours were correct. At an average of one hour per cycle, the costs of idle machines and their operators piled up.

So, the company decided to implement a centralized full-colour management workflow. The results were highly positive, as now no additional cycles are required to get colours right, except when the occasional request from a customer comes in asking to tweak a certain colour. Job costs have been reduced by 35 per cent, as each job requires less labour and the machines do not sit idle for as long as before.

There have also been qualitative improvements. For one thing, approval on press is immediate. With colours and greys always matching between all of the devices, employees now “walk in and walk out” of the production department, rather than fighting to adjust colours on the printer. For another, the company has achieved 20 per cent savings in ink consumption. This is significant given the high costs of inks for digital printers.

In general, the primary benefit has been faster turnaround with no press downtime. This greater efficiency is echoed in how shop employees do their jobs.

Further, there is greater customer confidence in the company’s capabilities now that colour quality is much more accurate. ‘Prestige’ brand owners are bringing in work that earns higher margins. As a result of reducing costs and earning these higher margins, profitability has increased substantially.

Setting the stage for growth

A centralized colour management system need not be expensive or time-consuming to implement. A decentralized system, on the other hand, can carry many hidden or underestimated costs, including the need for additional labour, materials and machine time, all of which whittle away at profit margins. When additional time is needed to prepare jobs for machines that sit idle, capacity is reduced, stress on the production floor is increased and revenue is missed. Even worse, business growth is limited, as clients begin to judge some of their specialized jobs too risky for decentralized colour management.

The implementation of a dedicated colour management system is recommended alongside a corresponding methodology, including the use of measurement devices to ensure colour accuracy throughout the design and printing process. By speaking first with experts, meeting proven standards and following quality assurance (QA) procedures, PSPs will be rewarded for their efforts.

Centralized colour management requires only a small investment of time and money, but offers a strong return on that investment by simultaneously reducing the cost per job and increasing print quality.

Bart Fret is director of large-format sales for GMG Americas, which develops colour management software. For more information, visit www.gmgcolor.com[1].

- www.gmgcolor.com: http://www.gmgcolor.com

Source URL: https://www.signmedia.ca/wide-format-printing-the-hidden-costs-of-decentralized-colour-management/